Learning by Launch: Inside the CubeSTEP Ambitious Space Mission

For many engineering students, astronautics is something studied, not practiced. They’ll look at theoretical equations on a whiteboard, see simulations on a screen and absorb knowledge through textbooks and lectures.

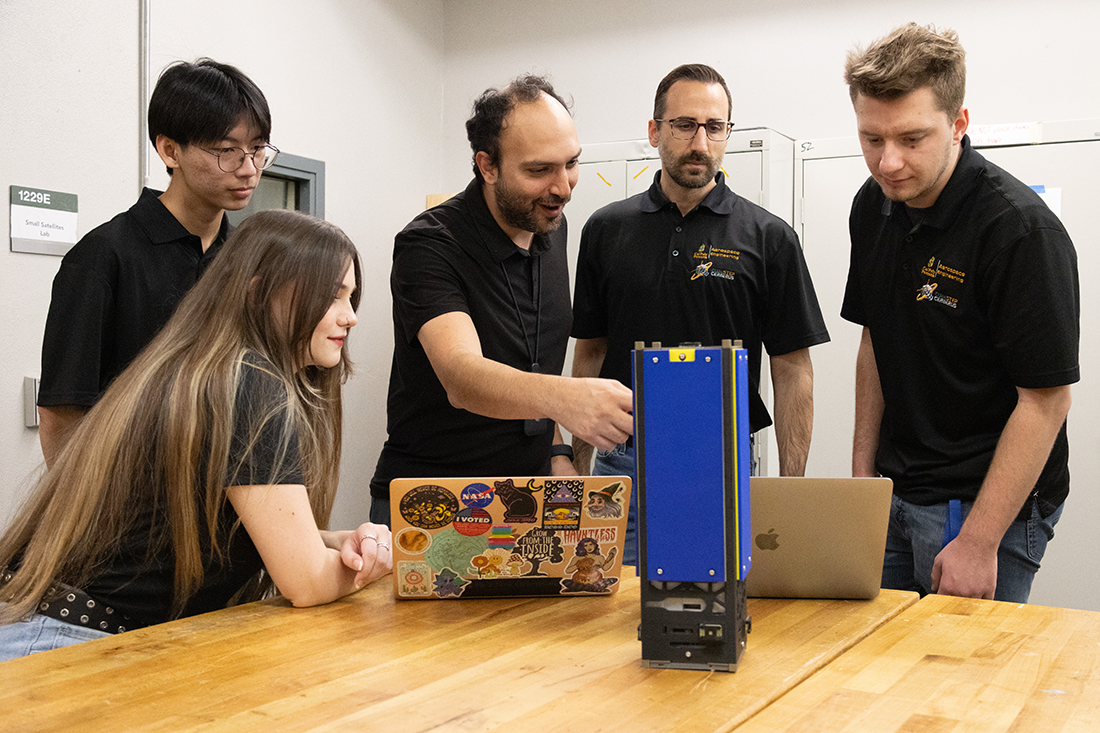

At Cal Poly Pomona, the CubeSTEP program does things differently. Under the direction of faculty lead Professor Navid Nakhjiri, CubeSTEP gives students the rare chance to design, build, test, launch and operate a spacecraft carrying real technology for a real client: the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

CubeSTEP was conceived not as a class or a club, but as a program for curious students to go hands-on with industry-funded astronautics projects. Students come out of the program transformed, discovering new passions, developing valuable skillsets and leveraging both to start careers.

A Real Mission, Not a Simulation

The inaugural CubeSTEP mission centers on a cutting-edge thermal technology developed at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL): additively manufactured oscillating heat pipes (OHPs). These devices passively move large amounts of heat through intricately printed internal pipes for spacecraft, like satellites, launched into space. The promise is enormous for future deep-space satellite missions where thermal management can determine whether or not a spacecraft survives.

The inaugural CubeSTEP mission centers on a cutting-edge thermal technology developed at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL): additively manufactured oscillating heat pipes (OHPs). These devices passively move large amounts of heat through intricately printed internal pipes for spacecraft, like satellites, launched into space. The promise is enormous for future deep-space satellite missions where thermal management can determine whether or not a spacecraft survives.

However, validating the technology via lab environments isn’t enough. Microgravity, radiation and long-duration exposure can fundamentally change how materials behave in space. Flying the technology is the only way to raise its technology readiness level for future missions. Doing that inside a NASA center would be prohibitively expensive. Doing it through the CubeSTEP program, where students are building a CubeSat (a miniature satellite about the size of a loaf of bread) with OHP technology, offers a cost-effective solution where students get hands-on experience with delivering real results to a actual client.

Once complete, the CubeSat will be a payload in a rocket launch in February 2027, where it’ll essentially hitch a ride to space. Students are responsible for the entire system: payload design, spacecraft integration, simulations, hardware testing, mission planning and operations.

“This is a great platform,” Nakhjiri says, “We can bring technology that JPL wants to test, build it on a CubeSat and fly it. It’s much cheaper than NASA doing it internally. At the same time, students going through this program have had the trajectory of their lives and careers changed. That’s what excites me the most.”

CJ Negrete (’25, aerospace engineering), former project manager for the program, said her participation in CubeSTEP was invaluable academically and for her career.

“What immediately stood out was that CubeSTEP wasn’t just a student project,” Negrete said. “It was a systems-driven program with real accountability, real constraints, and real stakeholders.”

Negrete immediately went straight to work after high school as a leader in Sprouts Farmers Market, opening stores across multiple states. By happenstance, she had the chance to visit the NASA Space Center when opening a new store in Houston. The experience served as a catalyst of her return to higher education 10 years after high school and eventually CubeSTEP. The experience gained as project manager was transformative. Today, she is a systems engineer at Sophia Space.

“CubeSTEP taught me how to think in systems. I worked across mechanical, thermal, avionics, and mission domains, learning how decisions in one area affect the entire architecture,” Negrete says. “That systems-level mindset directly influenced my transition into my current role.”

Building Capability from the Ground Up

When the program began in 2019, Cal Poly Pomona did not yet have the infrastructure required to support a mission of this complexity. Over several years, Nakhjiri and his team built it piece by piece: a spacecraft clean room for assembly, specialized testing labs reconfigured for CubeSat-scale hardware, and now a dedicated mission operations center to command the satellite after launch.

When the program began in 2019, Cal Poly Pomona did not yet have the infrastructure required to support a mission of this complexity. Over several years, Nakhjiri and his team built it piece by piece: a spacecraft clean room for assembly, specialized testing labs reconfigured for CubeSat-scale hardware, and now a dedicated mission operations center to command the satellite after launch.

Further, many of the analyses CubeSTEP requires—advanced thermal modeling, space-qualified design practices, mission verification—aren’t covered in undergraduate coursework. Students in CubeSTEP learn them by doing, guided by co-advisors Nakhjiri and Assistant Professor Marco Maggia, industry mentors, and engineers at JPL. Several students spend summers embedded at JPL itself, working full-time internships aligned directly with CubeSTEP’s technical needs, then bringing that expertise back to the project

“Being part of a spacecraft from the very beginning… from idea to design to launch and operation, that’s not something many students can clai m,” Nakhjiri says.

Why Faculty Commitment Matters

Programs like CubeSTEP demand years of sustained effort—writing proposals, managing grants, coordinating industry partners, mentoring students across multiple cohorts and carrying technical responsibility for hardware bound for space. That level of commitment goes far beyond a typical teaching load.

Programs like CubeSTEP demand years of sustained effort—writing proposals, managing grants, coordinating industry partners, mentoring students across multiple cohorts and carrying technical responsibility for hardware bound for space. That level of commitment goes far beyond a typical teaching load.

Nakhjiri took it on deliberately. Coming from a background heavy in theory and numerical work, he saw at Cal Poly Pomona an opportunity to close the gap between theory and practice and build something that would actually launch. He also saw how transformative that experience could be for students. Graduates of CubeSTEP don’t just understand aerospace systems. They understand what it means to start and complete a real engineering project with real stakes.

“Most of my students who worked on CubeSTEP ended up in roles directly related to what they did here,” Nakhjiri says. “These students can say, ‘I’ve designed something that flew. That changes everything.”

The outcomes reflect that. Of the students Nakhjiri has kept in contact with, roughly 85% are now working in aerospace roles or pursuing advanced study directly related to their CubeSTEP responsibilities. Many stepped into jobs that mirrored their project role, like systems engineering, thermal design additive manufacturing.

“The confidence I have in navigating complex systems, asking the right questions, and balancing technical rigor with practical execution traces directly back to CubeSTEP,” says Negrete. “It bridged the gap between academic learning and real-world engineering in a way that few programs truly do.”

Industry Funding Makes It Possible

This opportunity only exists because of external funding partners. The bulk of the funding comes from an approximately $900,000 NASA award in 2023. Before this, CubeSTEP was built on years of smaller investments and demonstrated capability.

This opportunity only exists because of external funding partners. The bulk of the funding comes from an approximately $900,000 NASA award in 2023. Before this, CubeSTEP was built on years of smaller investments and demonstrated capability.

Much of that funding flows directly back to students as it pays for internships at JPL, travel and hands-on work that might otherwise be inaccessible. It’s a model where education, research, and workforce development create opportunities for engineering students to do real, hands-on work.

What’s Next

For the CubeSTEP team approaching launch early next year, the excitement is real, but so is the pressure. Regardless of the outcome, the educational impact is already complete.