Eagle Rock Elementary School

Eagle Rock Elementary School is a public elementary school in Northeast Los Angeles. It’s a 1920s Los Angeles suburb in its own small valley surrounded by hills. Founded in 1910, Eagle Rock was its own city for a mere ten years. As with many smaller cities in the area, it was annexed to the growing city of Los Angeles in order to have access to its water and energy infrastructures. California State Route 134 and California State Route 2 now define the northern and western edges of the community. Pasadena lies to the east. And to the south is Highland Park—a hotbed of gentrification protests over flipped houses, new businesses, and low-rent apartments being converted into high-rent luxury lofts. The community is part of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the second-largest school district in the country. Over half of its students qualify for free or reduced-cost meals. Which makes it a Title I school eligible for federal funds to help schools with large numbers of low-income students meet educational goals. Once marketed as a haven for White families escaping the city, it is now one of Los Angeles’s most diverse neighborhoods. Nearly 80 percent of the students are Hispanic or Filipino. 1 Eagle Rock Elementary has so far maintained—and benefits from—its cultural and socioeconomic diversity despite its adjacency to Highland Park. The rising rents and home prices of Eagle Rock could endanger affordability and diversity. Two new affordable housing developments along the main boulevard might help.

This was my children’s school, and it had a lot of things going for it. An elegant and welcoming entry in a 1920s historic building was approached along a wide, grassy parkway shaded by hundred-year-old deodar cedars. The school sits a block away from where the two main boulevards cross. Once routes for Red Car trolleys that served the Los Angeles metropolitan region, they are now major automobile thoroughfares—too wide, too fast, and not designed for pedestrian safety. Many students walking or biking to and from the school cross at least one of these six-lane roads.

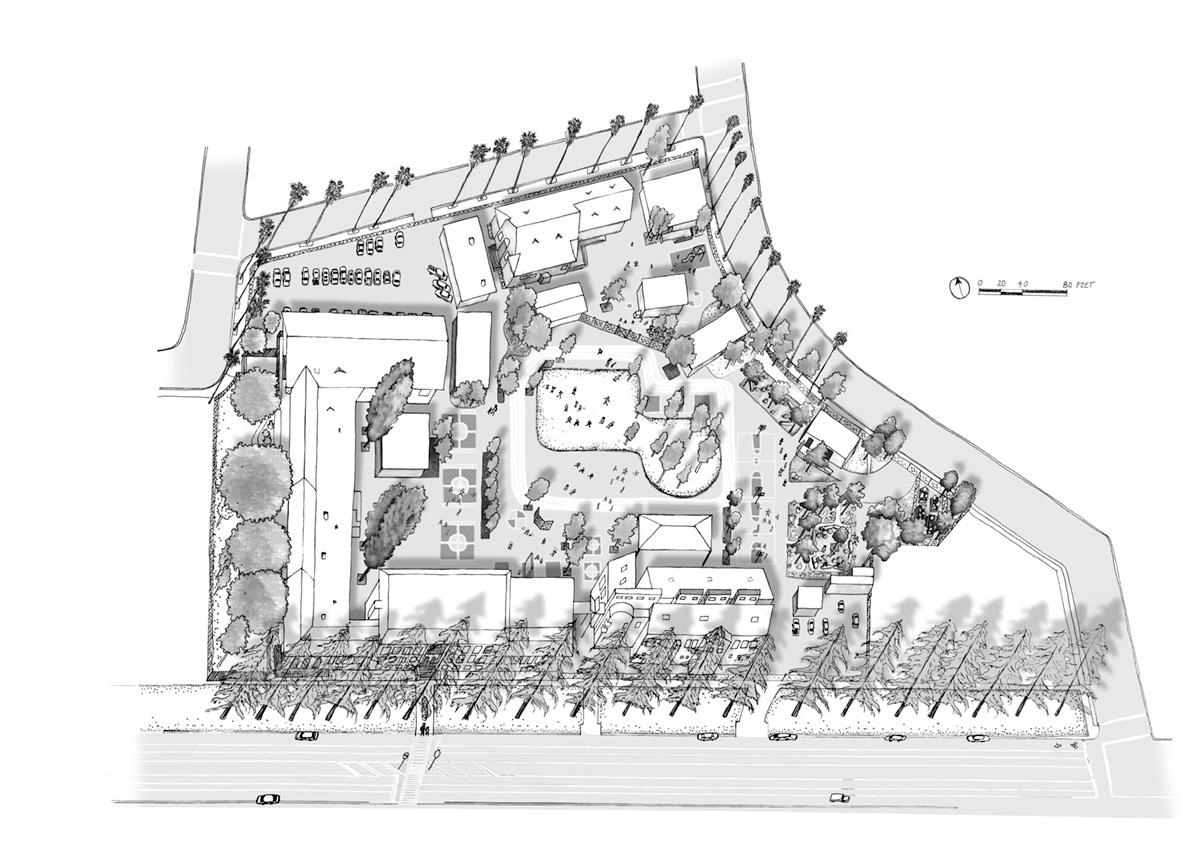

On my children’s first day of school, we stood, stunned, staring at the bleak asphalt yard inside the school walls. It felt so different than the grassy yards the kids and I knew in all our previous schools. Four years later, I taught a landscape architecture studio that partnered with my son’s class to redesign the playground. This inclusive design process engaged second and third graders in reimagining what their school could be. My students taught them watershed health concepts through a mapping exercise requested by their teacher to meet a curriculum requirement. The Cal Poly Pomona students worked with the Eagle Rock Valley Historical Society and local ecological artist Jane Tsong to understand the historical water and settlement patterns, which suggested that Eagle Rock Elementary sat close to or over an old stream corridor. This helped explain the basement flooding during heavy rains. Then they developed concept designs based on their work with the elementary students. A couple of years later, a group of parents applied for and won a California Proposition 84 Stormwater Grant to improve the site.

Environmental nonprofit Los Angeles Beautification Team hired landscape architecture firm Studio-MLA to manage the design and implementation of the living schoolyard. In one of those small-world moments, I worked there at that time and got to design and manage the project. The process benefited from my existing relationship with the community and commitment to the school. The PTA President at the time, Occidental College economics professor Bevin Ashenmiller, engaged her colleague, Occidental College behavior researcher Marcella Raney, to study the school. Raney and her students observed which playground areas were well used and which weren’t. These observations were critical for the design. The places that invited a lot of physical activity were kept as they were. The underused places—such as the enormous and exposed center of the playground—were where we focused our changes.

The final design replaced 21,000 square feet of asphalt with soil and mulch, native plants, permeable surfaces, and grass. Twenty-four new shade trees increased the tree canopy to provide protection from the sun and provide green views from classroom windows. A new learning garden—its small hills planted with fragrant California native sages, buckwheat, and grasses—provides a sense of “being away,” essential to reducing stress. 2 Stumps and logs, placed just far enough apart to invite students to leap from one to another to another, double as an outdoor classroom. The underused middle of the playground became a grassy kickball field and tree-covered park space. The logs and grass and boulders spread throughout provide plenty of places for students to sit, rest, walk, and lie down. Two rows of trees standing in long, shallow trenches covered in mulch intercept rainwater as it runs down the playground to the storm drain. These tree planters and the large grassy play field work with nature to allow rain to recharge the groundwater basin and clean the runoff instead of allowing pollution through the drain and into the Los Angeles River. The design broke up the large expanse of asphalt to create smaller, shadier play spaces and includes native trees and plants, boulders, logs and stumps, and mulch areas. The design supports the health of all species—human and otherwise. Trees and plants selected from the local plant communities need little irrigation or maintenance and provide vital habitat for birds, butterflies, insects, and soil biota. LAUSD policy dictates organic management and maintenance practices to protect students from chemical exposure.

Before the playground improvements, Principal Stephanie Leach worked with teachers and playground monitors to remove any playground rules limiting students’ choice of activity and play area. Allowing free play was essential for Raney to measure the impact of the physical changes on students’ behavior. Buchanan Street Elementary School, two miles away in Highland Park, served as the study’s control school. The most popular recess activities before creation of the living schoolyard included handball, kickball, tetherball, and four square. After the playground became a living schoolyard, the most popular activities were tag and chasing, gymnastics (handstands and cartwheels), climbing, jumping, and making up games.

“Handball was one of the most popular activities before the greening,” Raney told me. “But not after.”

“After greening, the kids who were already active didn’t change their activity,” she said. “That’s fine.” But the number of kids who were not doing anything at recess fell dramatically.

“At the beginning, nearly 55 percent of all students were sedentary or standing. Then, when we greened, now 46 percent were sedentary,” Raney said. “Thirty to forty new students were now active who before didn’t move at recess.” And even those who were not active chose to sit or lie down in the learning garden or on the lawn, where they were immersed in the nurturing qualities of nature. Though the improvements included dozens of stumps and logs that were sanded and finished to lie flat on the ground and minimize splinters, tippy and odd-shaped stumps prove to be kids’ favorites. A selection of stumps, some split in half, invite students to test their balancing skills by rocking back and forth on one end or by placing their feet on the flat side of a half stump, rocking with the round side against the ground.

The most popular places for students to play on the greener schoolyard were the stumps, logs, and mulch areas. These types of play settings, made with natural materials and loose parts, encourage creative play and cooperative social play. With the emphasis on socio-emotional learning in schools, providing play opportunities that support this is no small matter. It worked. Among Raney’s findings was a 50 percent decrease in antisocial behaviors after the schoolyard improvements were made. 3

Eagle Rock Elementary was honored with a US Department of Education Green Ribbon Schools Award for its innovations to improve human and environmental health and education. The awards honor pre-K through twelfth-grade schools that reduce environmental impact and costs, improve health and wellness, and educate students about the environment and sustainability. Eagle Rock Elementary’s living schoolyard helps cool and clean the air, absorbs and cleans stormwater runoff, provides wildlife habitat, and sequesters carbon in addition to supporting students’ health and well-being. The planting design plans for the future, too. The need for shade was immediate and urgent. Riparian tree species were planted in the lawn and rain strips. But the learning garden revolved around the oaks that grow slightly higher in the natural ecosystem, and they grow very slowly. Fast-growing, shorter-lived Tipuana tipu trees, planted between the oaks, provide quick shade while the oaks grow in, and they can be cut and used for more seating once the oaks start providing real shade.

After just three years of growth, the trees provided shady play places throughout the yard. The rows of trees on each end of the playground divide the main play area and create roomlike places where students can experience feeling apart from others.

Principal Leach said that teachers came to her after the living schoolyard was finished, saying their students come back to class after recess ready to learn, without needing to be redirected as usual. They’ve gained time to teach. The week after the living schoolyard opened, she told me she took one of her students with autism spectrum disorder out to the learning garden while he was acting out. She said that upon sitting on one of the logs, he immediately and visibly calmed down, looked around, and declared this was his classroom.

Three years later, when I revisited the school, Principal Leach told me, “A parent thanked me this morning for the sense of community in this school. The greening built that and sustains it because it’s a living thing.”