The most remarkable development in global politics in the last half century is the appearance of those forces and ideologies that seek to unravel the promise of human freedom altogether. Only now they act in the name of human freedom and democratic values and come to power through legitimate means, even as they undermine public trust in democratic institutions. In the United States, elected officials of one of two major political parties can now openly—and routinely—claim, to immediate global broadcast, that the US must not be a democracy at all. And that instead, it was always meant to be a republic of individual freedoms. What does this symptomatic perversion of our political theory and democratic history mean for the future of liberalism and civil rights in the age of data mining and culture wars?

We believe that the future of democratic politics and political solidarity cannot be imagined, let alone secured, without a firm understanding of this long arc of democracy’s raging present and, more precariously, the dystopian shapes that its aftermath is poised to take. Because attacks on democracy today come from within—and inside—the citizenry in a manner and with frequency never seen before, this is an existential moment for our faith in the idea of citizenship at large. Reactions against movements for social and racial justice—or against legislation that seeks to address global wealth inequality and access to food (or even air-conditioning)—are thus no more fundamental to understanding the future of democracy than they are windows into mutations of human nature itself.

The most visible form of violence in liberal democracies appears today as partisan conflict and strategic neglect of the vulnerable and of infrastructures that might better their lives. We witness today not simply a violence driven by ideological commitments and disagreements but instead indifference and the willingness to kill over questions of identity.

At The Democracy Institute, we define conflict as this long, catastrophic process that has normalized the desire to kill in liberal democracies, sometimes by force and often by pure neglect of the caste, religious, and racial minorities. Distinct from tangible violence, it is a process that has elevated disagreements and differences of social and political choices into matters of existential strife. They have turned arguments about political decisions and public goods—safety, policing, and increasingly, education—into matters of life and death.

As conflict has moved from borders to inside our cities, democracies find themselves at the threshold of an endless social strife marked by the readiness to kill those who simply vote or dress differently.

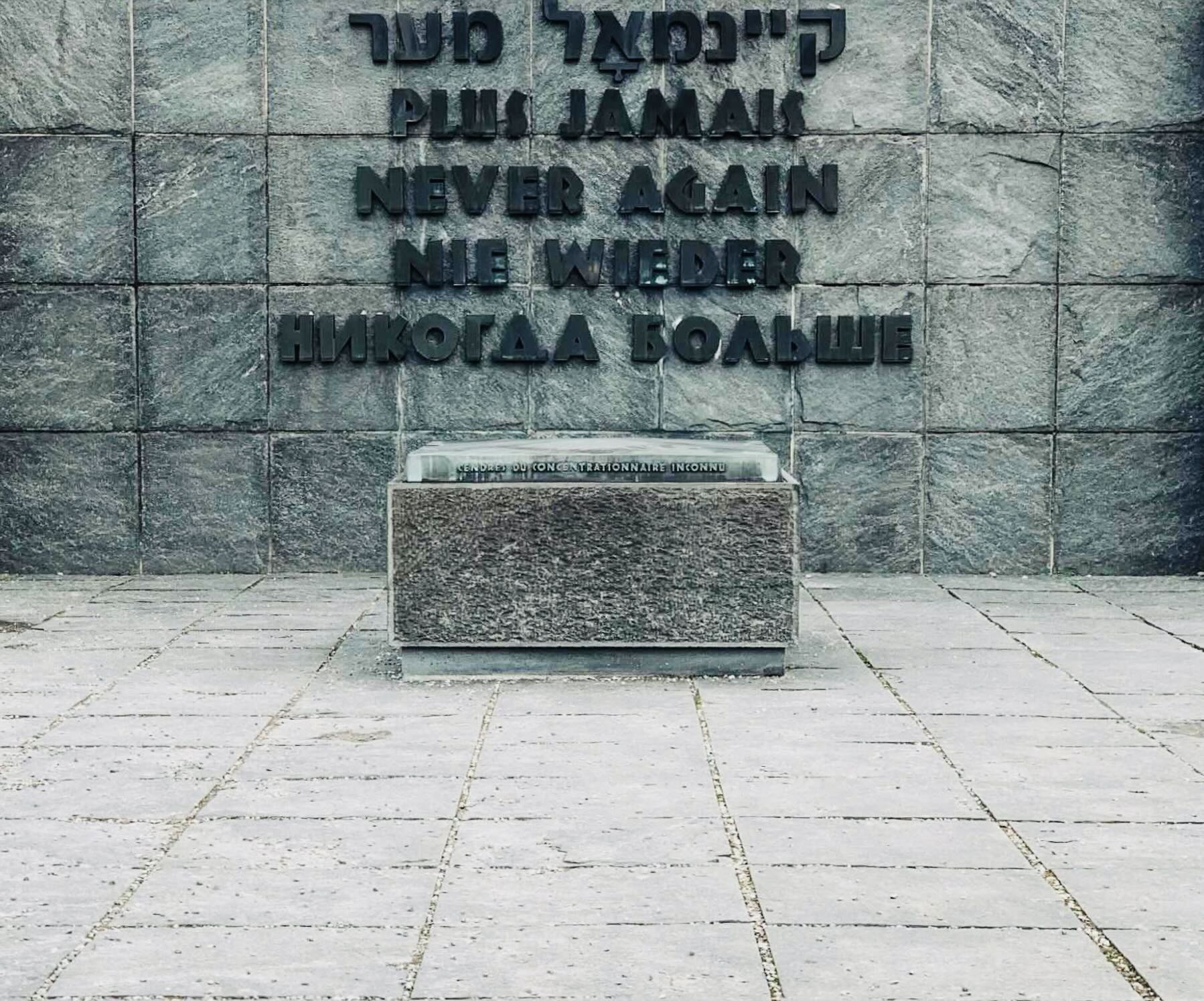

How might liberal democracy exit this existential, destructive, and suicidal impasse into which it has not only pushed itself but also its purported enemies beyond? Two decades of war on terror might have suppressed the European and American appetite for wars in the Middle East. But those retreats if not defeats—in Afghanistan most recently—still haven’t brought home the lessons about how to leave the battles behind. Violence ebbs and flows, but conflicts continue, if only by other means, within and beyond our physical borders and moral boundaries, and with only a semblance of postwar institutionalism left in place today to meaningfully separate liberal democracies from their authoritarian, populist, sovereign, and electorally popular enemies.

We seek to investigate not simply the infrastructure of this perpetually imminent and impending violence worldwide but rather its legal and political logic, and above all, the effect this violence—often endorsed by majoritarian will in the world’s most populous nations—might have on the future of the modern constitutional compact.