Lin Ong’s research with the Asia School of Business explores how refugees navigate life without legal status and how new digital wallet policies could reshape economic access

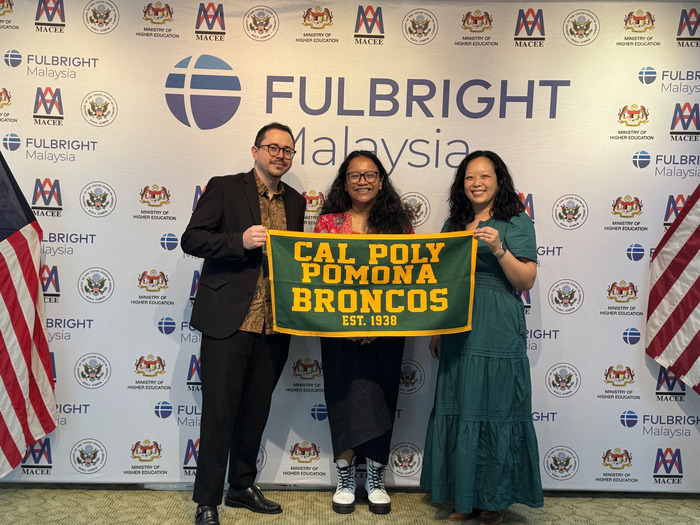

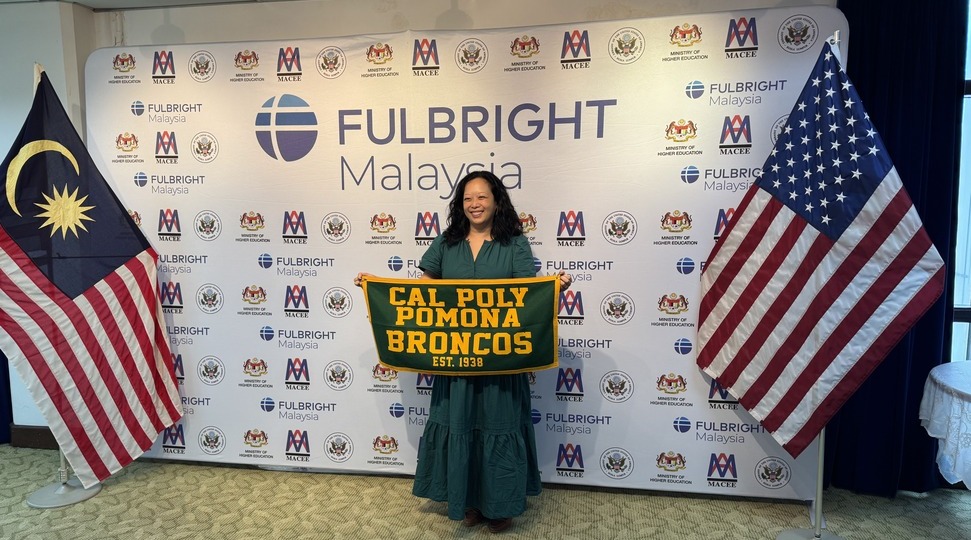

Lin Ong’s research with the Asia School of Business explores how refugees navigate life without legal status and how new digital wallet policies could reshape economic accessCal Poly Pomona Assistant Professor of Marketing and International Business L. Lin Ong recently returned from Malaysia after serving as a Fulbright U.S. Scholar, hosted by the Asia School of Business (ASB) in Kuala Lumpur. Her work, supported by the Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange (MACEE) and the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA), focused on refugee financial inclusion and youth experiences in a country that hosts one of Southeast Asia’s largest refugee populations.

Ong was born in Malaysia and immigrated to the United States as a child. Returning as a professional academic, and as a parent, added personal depth to an already ambitious research agenda.

| “Malaysia hosts more than 180,000 refugees and asylum-seekers, the vast majority from Myanmar. Because the Malaysian government has not signed the U.N. refugee convention, refugees have no official legal status, cannot open bank accounts, and face barriers to education, health care and employment. Ong’s Fulbright research examined how refugee communities use informal financial systems, and how emerging digital wallet programs—launched cautiously in partnership with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)—may expand economic participation.” |  |

Through ASB and her longtime colleague Melati Nungsari, Ong interviewed community leaders, youth, business owners and financial-service executives to understand how refugees navigate daily life and systemic exclusion.

What led you to apply for a Fulbright in Malaysia?

I was born in Malaysia, and all my extended family still lives there, but I had never lived there professionally. When I applied for the Fulbright, I knew I wanted my kids to come with me so they could spend time with their great-grandmother and relatives. My mom traveled with us and helped with childcare. It was complicated to plan, but a meaningful opportunity to reconnect with my culture and family.

Did returning feel like going home?

In some ways, yes. In others, it was like visiting a completely different place. Malaysia has changed dramatically since my parents’ generation—it’s now a few years away to becoming a high-income country. My mom would look around and say, “I don’t recognize this.” Being there with her allowed me to see how much the country has transformed.

What was your Fulbright placement like?

I had an ideal setup. There were five Fulbright faculty scholars in Malaysia that year, and we supported each other through attending each other’s presentations and events, and communicating in a group chat. My host was Dr. Melati Nungsari at the Asia School of Business. We’ve known each other for about 20 years, and we had an optimal research fit—she works with UNHCR on refugee policy, which aligned closely with my interests.

|

|

Established in 2015 the Asia School of Business (ASB) is an AACSB-Accredited institution committed to developing transformative and principled leaders who will create a positive impact in the emerging world and beyond.

|

What were you researching?

My work looks at vulnerable consumers, and in Malaysia I was able to extend this research lens to refugee entrepreneurship, especially how people start businesses without access to formal banking or legal recognition. Malaysia is considered a transit country for refugees, and their lack of legal rights is supposed to encourage refugees to resettle elsewhere. However, the lack of resettlement opportunities means that refugees often must stay “in transit” (whether in Malaysia or another country) for years. Without legal rights, refugees in Malaysia can’t attend public school, legally work or open bank accounts, making them vulnerable to exploitation, theft and extortion.

We studied refugees’ financial lives—how they earn and save money, how they pay for services, and how informal systems operate in the absence of legal protections.

A significant policy change happened while you were there. What was it?

UNHCR partnered with a major Malaysian e-wallet company to allow verified refugees to open mobile wallet accounts for the first time. It’s limited, but it’s a big step forward to financial inclusion. If a refugee has completed UNHCR verification—which can take one to two years—they can apply for an e-wallet account. It helps legitimize their businesses and protect them from cash-related issues. For example, community leaders shared stories of people carrying large sums of cash to pay hospital bills and being robbed on the way. The risks are constant.

How did you and your colleagues study the rollout?

Through ASB, we were able to interview CEOs and leaders from the financial services side. We also interviewed around 30 refugee youth, who are digital natives and often the ones helping their communities to access this new technology. We found that the onboarding process is difficult, and limited financial literacy and refugee-specific issues with identification (such as changing addresses, language barriers, and misunderstandings) can result in applications being rejected over small errors, which prevents individuals from reapplying for another 2-4 weeks.

Even among the youth interviewed, about half couldn’t get approved, which shows the onboarding issues still present in the new system.

|

Looking Further: About 85 percent of Malaysia’s refugees are from Myanmar, including Rohingya Muslims and other ethnic minorities facing persecution. The remaining 15 percent come from countries such as Somalia and Afghanistan. Despite their skills or education levels, refugees cannot legally practice most professions. Many work in informal food service, construction or small-scale community trade.

Ong’s research also intersected with a separate ASB project studying Afghani women enrolled in an NGO entrepreneurship program. Over a year of interviews, the team tracked how these women’s household dynamics shifted as they gained business skills and financial confidence

|

Can you share more about the work with Afghani women entrepreneurs?

That project involved six rounds of interviews over a year. These women came from a culture where they were discouraged from working outside the home. Through the entrepreneurship program, they developed new confidence and agency. We interviewed two husbands as well, and both said they’d become active partners in their wives’ businesses. Seeing that shift—recognizing women’s abilities and contributions—was incredibly powerful.

Did you teach while at ASB?

I didn’t teach formal classes, but I gave lectures and worked closely with research assistants. One assistant was assigned to work directly with me, and she helped conduct and transcribe interviews. We’re still collaborating on research today.

How often had you returned to Malaysia before this Fulbright?

As a kid, my family went every three years. As an adult, I’ve gone about every five. My most recent trip was after Malaysia reopened its borders from COVID. I flew back immediately because I worried my great-grandmother might pass away, and I wanted the opportunity to see her one last time. Fortunately, I was able to spend time with her again during this trip.

You’re now the Fulbright Scholar Liaison at Cal Poly Pomona. What does that involve?

I work with the study abroad staff to encourage students to apply for the fully funded study program, and I provide support for faculty who are interested in applying. This year, after sending an email to all College of Business Administration, I met with around 20 students who were interested. Historically, CPP has had very few Fulbright students—maybe five total since the 1970s. This year we had about 10 applicants. Fulbright is such an incredible opportunity, especially for students who don’t see study abroad as financially possible. It’s funded by the U.S. State Department and covers airfare, housing and living expenses.

Did this experience shape how you view your role as an Asian American faculty member?

Absolutely. One reason I chose to teach at CPP is because I wanted Asian American students to see representation in front of the classroom. My upbringing was very high-pressure, and I try to show students that they can pursue paths that honor both their families and themselves. Being in Malaysia and talking to younger Malaysians—who are incredibly open-minded—was also eye-opening.

What do you hope people take away from your research?

That refugee issues are only going to become more urgent. Climate change, political instability and economic displacement are all increasing. Good intentions aren’t enough—we need to listen to communities directly and understand what they need. Solutions must come from the bottom up.