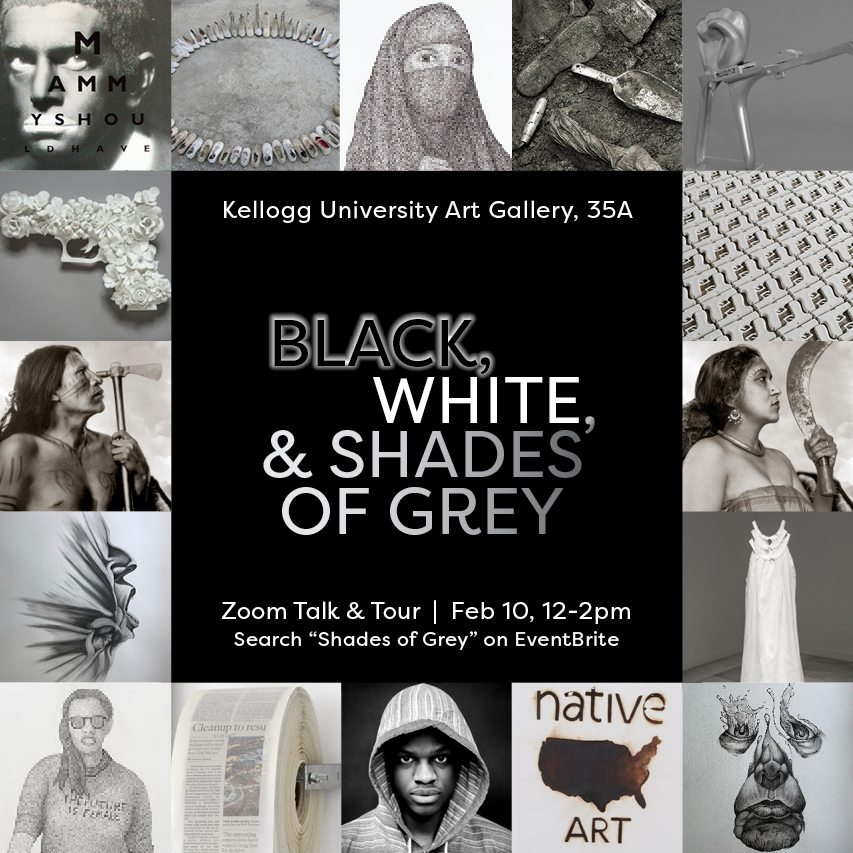

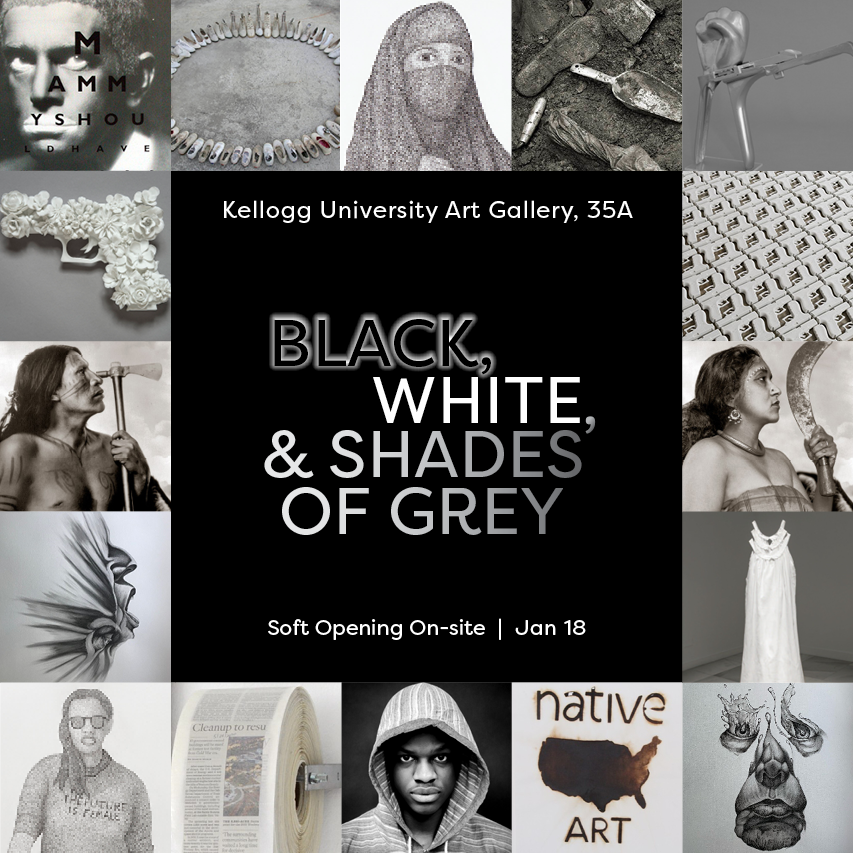

Black, White & Shades of Grey

Black, White & Shades of Grey

Jan 18, 2022 to Mar 27, 2022

Location: Kellogg University Art GalleryPress the tab key to view the content. Use the down arrow key to move to the next tab and up arrow key to move to the previous.

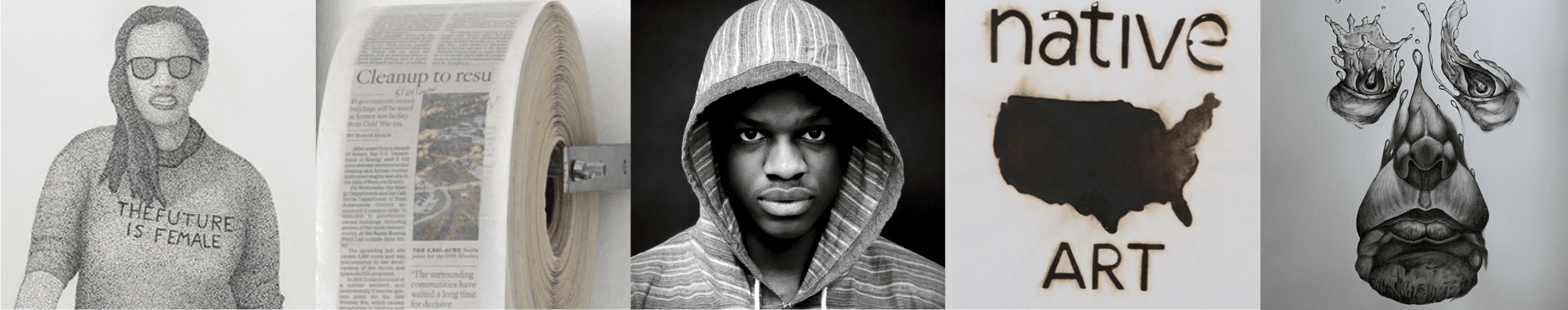

Black, White, & Shades of Grey features the artwork of several local, national and international artists of various ethnic backgrounds, colors and creeds that use mostly white, black, grey or sepia tones in their work to express their particular point of view. All address topics of the current socio-political, racial and ethnic, gender-based and cultural issues concerning many Americans today. As a campus with a very diverse student body, this exhibition is intended as a response to a polarized climate, in order to contribute to the dialog, and create an opportunity to influence and empower people of all ages, shades and colors by seeing artists like themselves represented. By showcasing visual voices that are not always seen nor heard, this exhibition is an opportunity to have this dialog.

Black, White, & Shades of Grey features the artwork of several local, national and international artists of various ethnic backgrounds, colors and creeds that use mostly white, black, grey or sepia tones in their work to express their particular point of view. All address topics of the current socio-political, racial and ethnic, gender-based and cultural issues concerning many Americans today. As a campus with a very diverse student body, this exhibition is intended as a response to a polarized climate, in order to contribute to the dialog, and create an opportunity to influence and empower people of all ages, shades and colors by seeing artists like themselves represented. By showcasing visual voices that are not always seen nor heard, this exhibition is an opportunity to have this dialog.

Thank you to a wonderful group of participating artists, who make all the difference:

Mariona Barkus, Chess Brodnick, Claudia Casarino, Gerald Clarke, Keiko Fukazawa, Mark Steven Greenfield, Bryan Ida, Walterio Iraheta, Tracy Keza, and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew.

Michele Cairella Fillmore, Curator Kellogg University Art Gallery Cal Poly Pomona January 2022

Black, White, & Shades of Grey features the artwork of several local, national and international artists of various ethnic backgrounds, colors and creeds that utilize mostly white, black, grey or sepia tones in their selected work to express their particular point of view. All address topics of the current socio-political, racial and ethnic, gender-based and cultural issues concerning many US Americans —and the world— today.

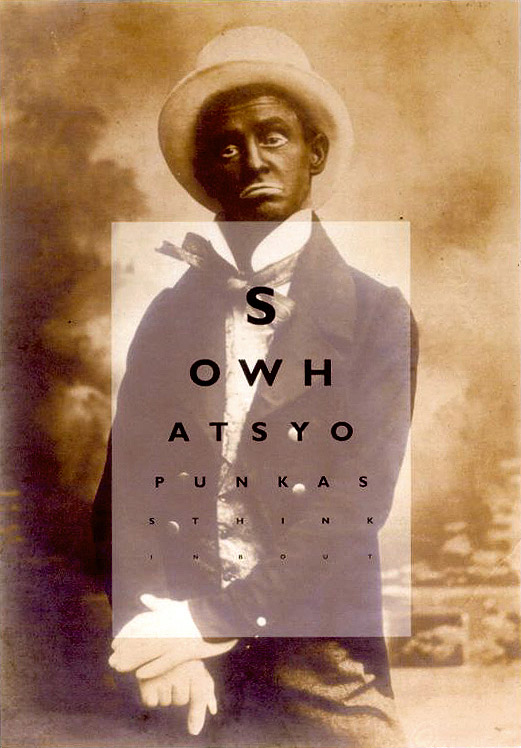

Artists Tracy Keza, from Rwanda, Africa, Mark Steven Greenfield, a local LA-Based artist, and African American, and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, East-Coast-based, Indian-born American, each address the often historically-misguided, ethnic stereotyping of already marginalized groups, with issues involving cultural appropriation, and systemic racism against Black Americans, Muslims, Indigenous Americans, Asian Americans and others, in their work. Through a juxtaposition of visual cues, images and concepts, these works may create “unease” —an unease most often caused by our own past misunderstandings and/or miseducation about the world, its peoples, and history. This “disquiet” is important to observe, absorb, contemplate and perhaps, embrace —because often, perspectives are based primarily on the place, and position, in which one stands at any given time in history.

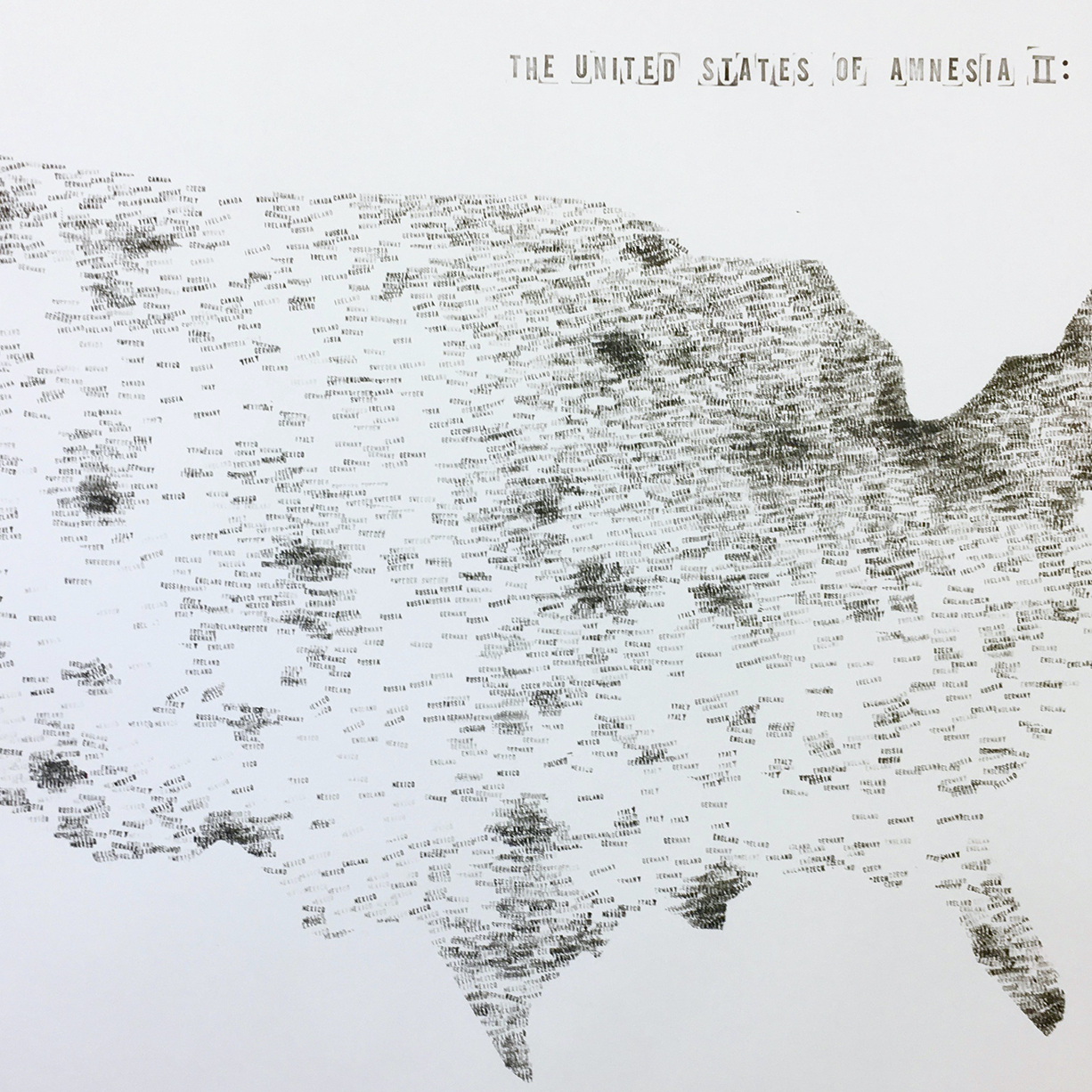

In unison with these three artists, and as an Indigenous American artist of the local Cahuilla tribe in the Anza Valley of nearby Riverside County, Gerald Clarke reflects upon the same topics within his work, and goes just steps further to recognize ‘immigration’ as it relates not only to the current day zeitgeist, but to our past American history as of a place that is, and formed by, a “nation of immigrants”. Walterio Iraheta and Claudia Casarino, both Central and South American, respectively, observe the effects of both forced and “elected” migration, while also tackling its root causes: poverty and lack of socio-political and environmental justice, created by a historical network of various interrelated circumstances and conditions. Their focus, in turn, is on the immigrant and migratory worker experience, and the consequential effects on the environment, local natural resources, and women and children.

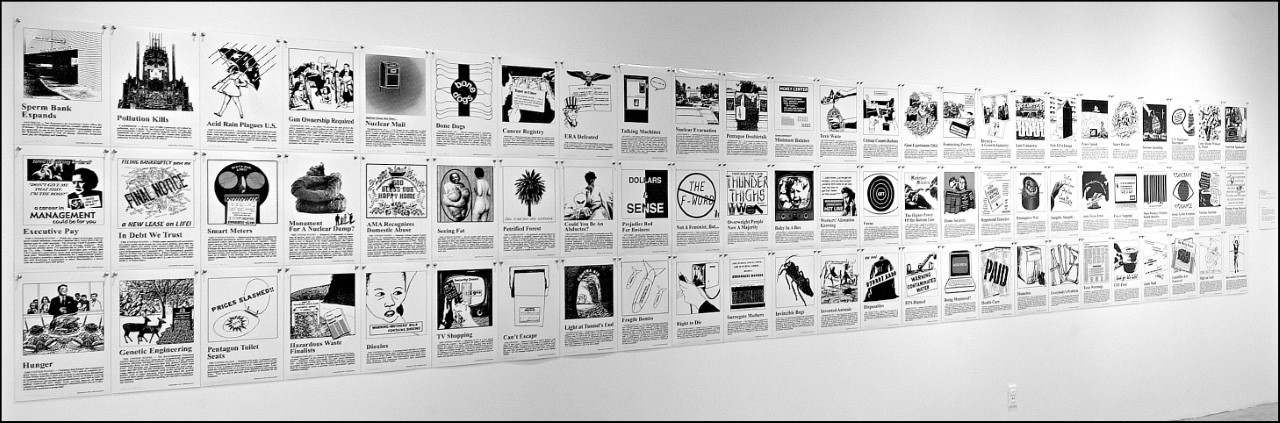

Also advocating for children and innocent victims, is local LA-based, Japanese-born artist, Keiko Fukazawa: her juxtaposition of pure white, delicate and florally-embellished porcelain used to make guns and assault weapons, address the gun violence that permeates America through mass shootings in schools, places of worship, offices and shopping centers. Repetitive multitudes of Glocks, made of the same pristine chinaware, are an embodiment of the numbers of gun deaths, per day, by gun violence. Also in tune with contemporary events, Mariona Barkus, a White LA-based feminist-artist, with an exhibition history that goes back to the Woman’s Building (a center for women artists formed in the 1970s), further advocates for the rights of women, our bodies, and that of Mother Earth. Her decades-long work, graphically documents over forty years of environmental abuses on our planet extracted from newspapers and other news media outlets over a pivotal, perhaps irreversible, time in our history. She acts both as an oracle, and an investigative archivist for environmental and social justice.

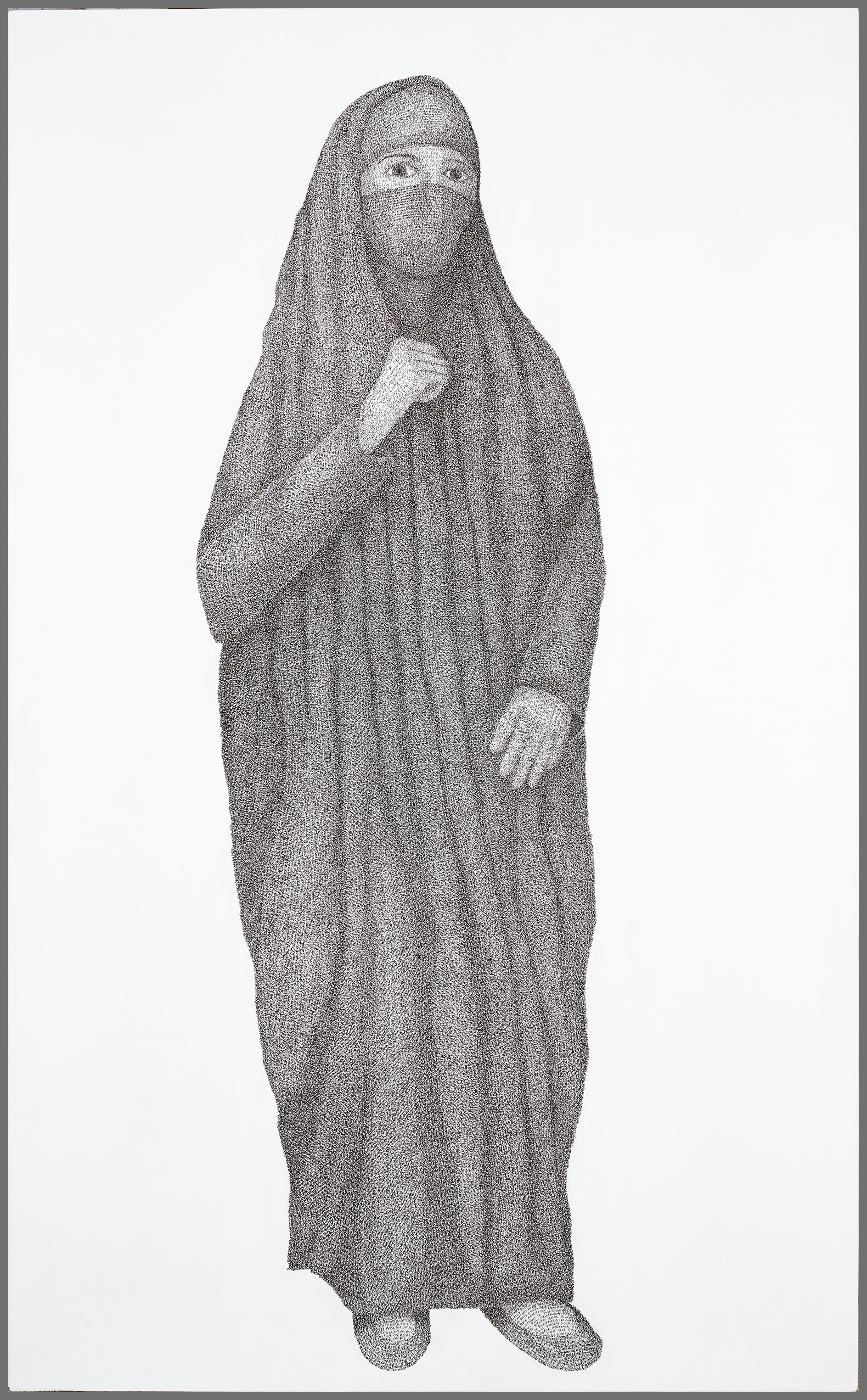

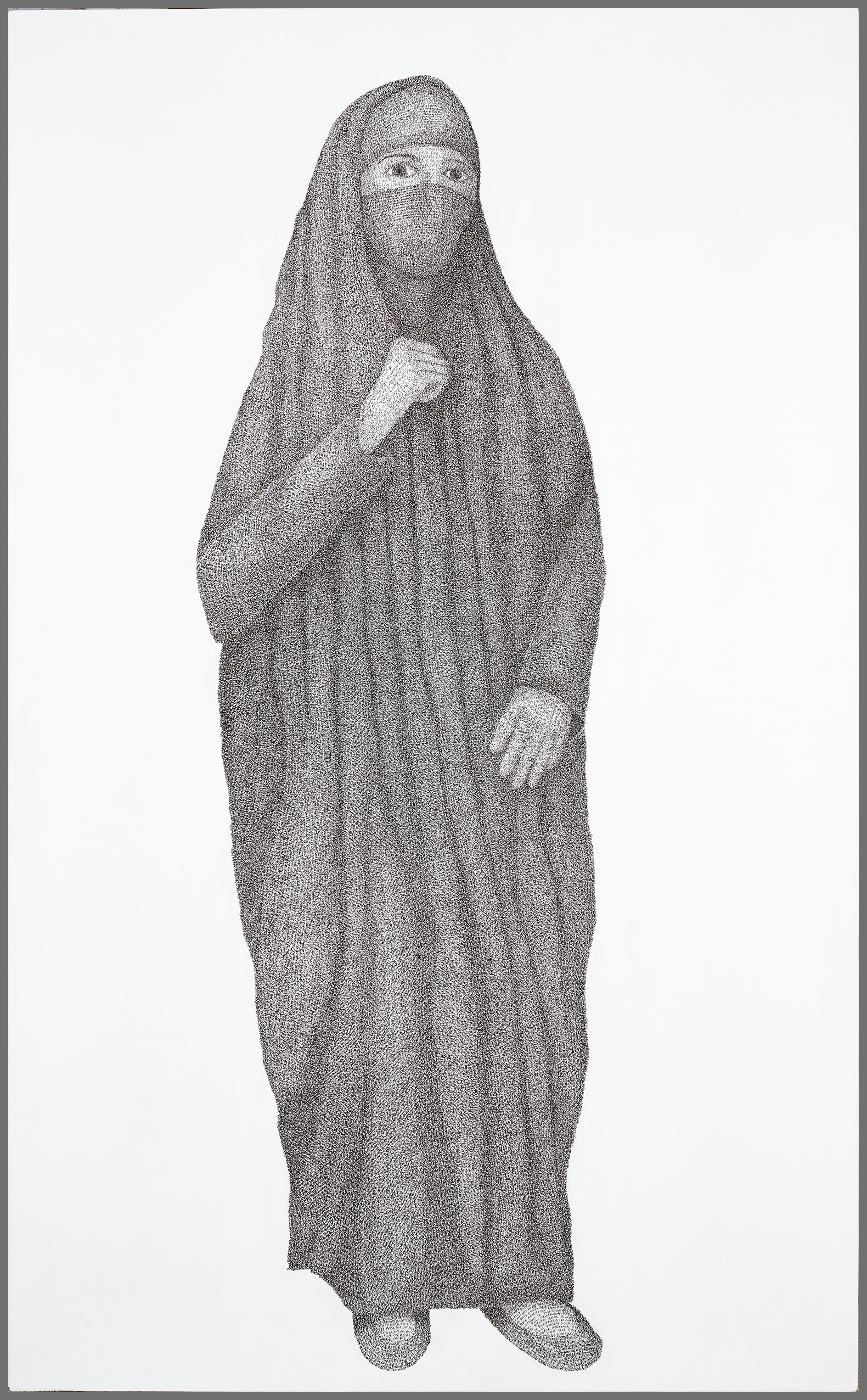

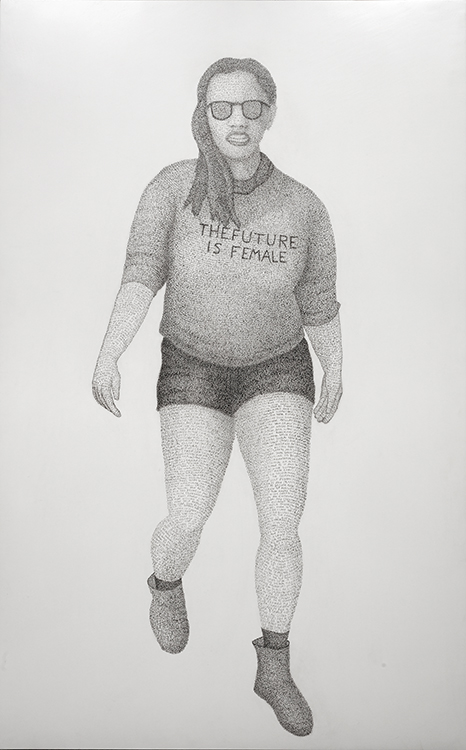

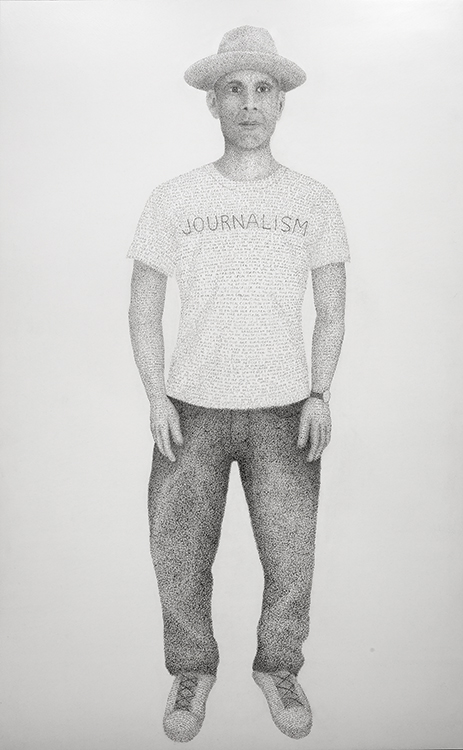

Bryan Ida, a storyteller, or chronicler of sorts, is an American of Japanese descent based in Los Angeles, who combines visually-verbal narratives together in a technique that is very unique —as unique as the people chronicled in his portraits. In a meticulous and fixated way, he transcribes a “personal story” about each individual depicted, who collectively personify diverse cross-sections of the varied cultures, races and religions existing in America. With their personal histories and embedded voices on display, these ghostly figures act as sentinels within the gallery walls, and stand as guardians, and custodians, of the space.

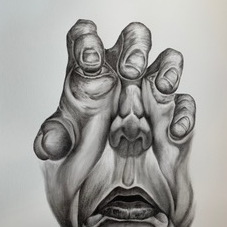

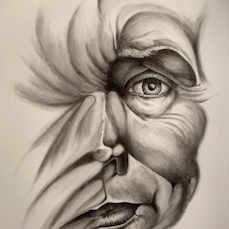

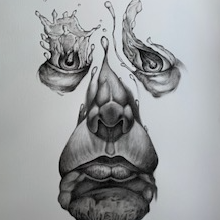

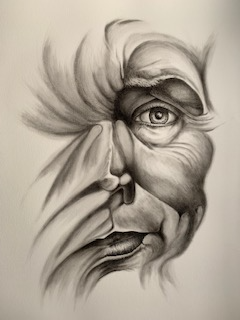

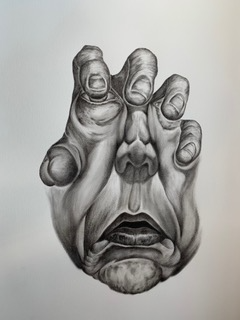

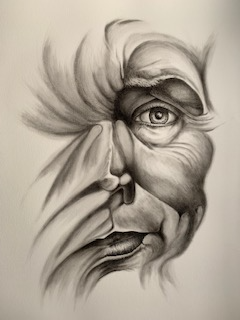

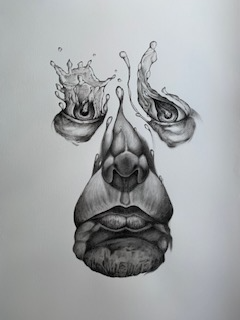

Peppered throughout each room of the exhibition, are the hand-drawn renderings by artist, and psychotherapist, Chess Brodnick. He too, is based in LA, and a White male. These largescale, exquisitely detailed images of the “White gaze” upon the rest of the artists’ works throughout the space, unveil his male countenance, often contorted and abstracted, broken and spliced, in ways that represent the greatest pain and angst felt by many in “White American” society today. The vestiges of the face are there, but they are more reflective of something turned inside-out —with the “internal façade” exposed for all to see— troubled, and sometimes even lost. It is an angst perhaps we can all relate to as humans, whether you are “White”, or a “Person of Color”. Alternately, if you are White —male, female, or even a “Karen”— it is easy to see the undercurrents of the societal reckoning going on today within Brodnick’s self-portraits. None of these works is intended to make excuses for Whiteness, or maleness, or even humanity, with all their/its faults. Nor is the work intended to target, or blame, White people for the dark parts of American history. Instead, these flustered faces are intended to spark a conversation about what sometimes feels like a “no-win” situation. But as any therapist might tell you, this disconcerted way of thinking, if reversed, can make all the difference: listening, learning, understanding, and action, can be a great way to start. And that is what this exhibition is about.

The nuances of each of these artists featured further the dialog into areas that reflect the societal impact on all of us. Some of their ways are subtle, and not done in a preachy or confrontational way, while others are more forthright in their intention. As we have learned through our own American history —recent or otherwise— confrontation, at times, can be a recipe for a better life (i.e., the Declaration of Independence, entering World War II, the Works Progress Administration); and when misused, can be an ingredient for lawlessness, and inciting violence. It is in the violence —not in the thoughts or words of intervention, nor peaceable assembly or protest— that we encounter problems that cause further division and vitriol. It is with the absence of violence and vitriol, and the presence of listening and peaceful dialog, we can make our perspectives clearer, hear and see others better, give voice to the often “voiceless and unheard”, in order build awareness, think more profoundly about our own personal actions and histories —and perhaps doing so in ways that are enlightening, self-reflective, and allow for respectful and meaningful growth.

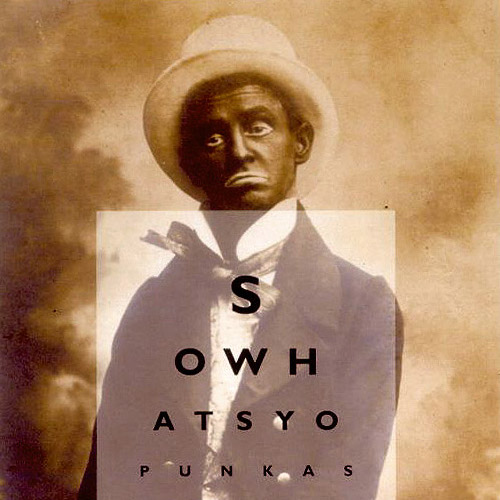

Images (top to bottom): Artwork by Annu Palakunnathu Matthew Belles, from the An Indian from India series, 2001 Archival digital print 12 x 19” The Belle of the Yakimas, ca 1899, Artwork by Gerald Clarke, The United States of Amnesia II, 2017 Paper, ink, rubber stamp 42x 54“, Artwork by Keiko Fukazawa, AKA AR-15-0416200732 (Blacksburg, Virginia), from the Peacemaker series, 2018 Porcelain, Plexiglass Case 39”W x 15”D x 6”H, Artwork by Bryan Ida, Neighbor, 2018 Ink on panel 60 x 37”, Artwork by Chess Brodnick, It begins at love, 2020 Sumi-e ink painting on paper 60 x 40”

Thursday, Feburary 10, 2022, 12-2 pm

Thursday, Feburary 10, 2022, 12-2 pm

Black, White & Shades of Grey Virtual Exhibition Talk & Tour

Join us on zoom for a tour of the virtual exhibition of Black, White & Shades of Grey! Click here to register on Eventbrite, or copy and paste bit.ly/3r7Sjue into a new tab.

Date: To Be Determined

POSTPONED: Jan 22, 2-4pm Opening Event Black, White & Shades of Grey Artists' Opening

Due to the shift to temporary remote instruction for the first three weeks of Spring 2022 semester, the Artists' Reception for the Black, White, & Shades of Grey Exhibition will be postponed until further notice. Tuesday, Janurary 18, 2022, 4-6 pm

Tuesday, Janurary 18, 2022, 4-6 pm

Black, White & Shades of Grey Soft Opening

Come join us for our soft opening at the Kellogg Art Gallery for the exhibition Black, White & Shades of Grey! This show includes the artwork of several local and national artists of various ethnic backgrounds, colors and creeds that use mostly white, black, or grey tones in their work to express their particular point of view.

Artist Biographies

Mariona Barkus

Originally from Illinois, Mariona Barkus moved to California in 1970. Her work reflects values and humor honed by her Midwest childhood experiences, which she characterizes as redemption through optimism in the face of adversity.

Barkus has shown her work in solo and group exhibitions throughout the United States as well as internationally in Ireland, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, and Spain, and is in the collections of the Yale University Art Museum, Getty Research Institute, Art Institute of Chicago, Franklin Furnace Collection at the Museum of Modern Art, Special Collections at the Whitney Museum of Art, Center for the Study of Political Graphics, Long Beach Museum of Art, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Lucy Lippard Collection at the New Mexico Museum of Art, UCLA, Indiana-Purdue University, among many others.

Her work has been reviewed in numerous catalogs and periodicals including: The Los Angeles Times and Artweek, among others. Some of the books featuring her work are Crossing Over: Feminism and Art of Social Concern by Arlene Raven; Other Visions, Other Voices by Paul Von Blum with a forward by Lucy Lippard; Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook by The Visual Studies Workshop; From Site to Vision: The Woman’s Building in Contemporary Culture, edited by Sondra Hale and Terry Wolverton, and most recently, from the University of California Press: American Artists Against War 1935—2010 by David McCarthy.

Barkus has received grants from the City of Los Angeles, Women’s Studio Workshop, and New York State Arts Council.

Chess Brodnick

Chess Brodnick is an American contemporary artist and psychotherapist specializing in the treatment of psychotic disorders. The latter has a great influence on the content and style of his work. Brodnick has not had formal training in the arts, instead has spent years researching techniques and time in front of the mirror, honing the skills needed to create images that resonate.

Over the last four decades, Brodnick has shown his artwork in the following venues: Alpha Contemporary Exhibits, Highland Park, CA; L.A.C.E. Community Gallery, Los Angeles, CA; LA ART, at both the Soho, NY and Encino, CA locations; Carter Sextons, North Hollywood, CA; Los Angeles Art Assoc. Gallery 825, Los Angeles, CA; Dab Art, Los Angeles, CA; and Las Laguna Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA. He has also participated previously in several Ink & Clay exhibitions at Cal Poly Pomona’s Kellogg University Art Gallery, winning the 1st place Curator’s Award in 2019 in Ink & Clay 44.

Claudia Casarino

Claudia Casarino was born in Asunción, Paraguay, and studied at the ISA of the National University of Asunción, with post-graduate residencies in New York, and London.

She has exhibited her work since 1998 and participated in five of the MERCOSUR Biennials, the Biennials of Havana, Tijuana, Busan, Cuenca, Curitiba, Algeria, and Venice, as well as the triennial of Santiago and Puerto Rico, and in various exhibitions in galleries, museums and cultural centers of Asunción, Santiago, San Pablo, Buenos Aires, Bogotá, Madrid, Barcelona, Milan, Amman, and London, among others.

Her work is included in the collections of the Museo del Barro in Asunción, Paraguay, Victoria & Albert Museum in London, Business Improvement District Council in Washington DC, the Spencer Museum in The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Sapin, and Casa de las Américas in Havana.

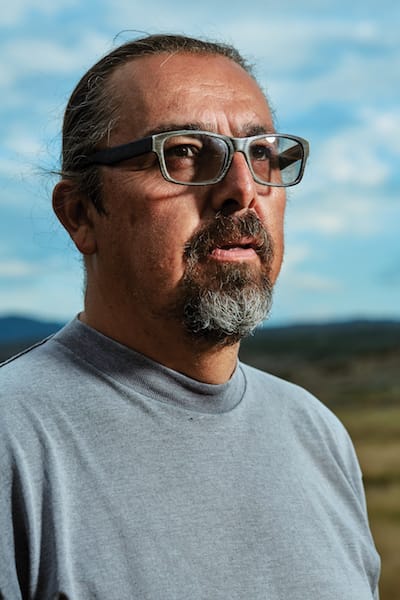

Gerald Clarke

Gerald Clarke grew up poor. His family had no money for toys, and he learned at a very early age to take good care of the few things his family had. If they broke, he fixed them or found new uses for them. This has made him very resourceful as a contemporary artist, which contributes to his inventiveness in using varied methods of art creation to express ideas. Although Clarke and his sister grew up in Hemet and Orange County, his father, Gerald Clarke Sr., regularly picked them up on weekends and hosted them for summers on the reservation with their extended family. “I grew up doing the cowboy stuff,” Clarke says. “I learned early on, that stereotypes are bullshit. My grandpa and my dad were hardcore Indian cowboys.” At a young age, he appreciated the wide-open spaces of the reservation to wander, play and participate in the tribe's cultural activities. He was a very sensitive and empathetic kid and still carries those traits with him today in his work.

His elementary school was progressive in terms of arts education and so, he immediately excelled in the arts. He received several awards his art class projects. Clarke’s ability to "build" and "fix" was translated into his efforts in drawing, printmaking, sculpture, and more. He was passionate about learning. Clarke went to college and earned Master's Degrees in Painting and Sculpture from Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. He became an educator, knowing all along that his heritage would eventually lead him back to the reservation. “From the time I was very young, I knew it was my role to take over the ranch after my dad died,” he says. That day came in 2003, when Clarke was teaching studio art at East Central University in Ada, Oklahoma. He gave up his position, returned to the ranch, and began teaching part time at Idyllwild Arts, where he later became chair of the Visual Arts Dept.

Clarke has emerged as a tribal leader and is back on the tenure track as an Assistant Professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Riverside. But neither he nor his tribe is stuck in a time warp; the reservation has plenty of modern amenities: a bright-white internet repeater towering on a hillside, a softball field situated across from a new ramada, solar panels on several rooftops, and Clarke’s art studio, a Quonset structure he built two years ago.

For the past 25 years, Clarke has been creating poignant, conceptual, and often humorous art addressing Native American identity and its intersection with mainstream U.S. culture and politics while defying the trappings and stereotypes of Native art. Clarke cherishes the opportunity to exhibit his art where Cahuilla tribal members can see it. “For me, success is being respected in my community,” he says. The contemporary art world's emphasis on the individual "genius" and the "cult of celebrity" are in direct opposition to the traditional beliefs Clarke was raised with. While many contemporary artists stress the importance of self-expression, Clarke feels the weight of the responsibility he owes to his ancestors. He believes self-expression is as natural as breathing and does not want to focus on it at all. Instead, Clarke focuses on trying to make art that is honest to the life he has led as a contemporary Native person.

Keiko Fukazawa

For over 35 years, ceramic artist Keiko Fukazawa has created work in multiple national and cultural contexts, embracing a cultural hybridity that says, “anything goes.” Her recent residencies in Jingdezhen, China, known as the “porcelain capital” of the world, have sharpened and expanded her perspective, inspiring her to further push social and cultural boundaries with conceptual art.

Fukazawa’s work has been widely exhibited in museums and galleries in the U.S. and around the world, including: Los Angeles, CA; New York, NY; Medellin, Colombia; Toronto, Canada; Taipei, Taiwan; and Perugia, Italy. She has shown one-person shows at: Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles; Gerald Peters Contemporary, Santa Fe; Garth Clark Gallery, Los Angeles and New York, and numerous group shows at California State University, Los Angeles, and the University of South Florida, Tampa. Museum exhibitions of Fukazawa’s work include: Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); USC Fisher Museum of Art in Los Angeles; American Craft Museum in New York; and Arlington Museum of Art in Texas. Her work is in permanent collections at the National Museum of History in Taipei, Taiwan; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; and Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin.

Fukazawa’s art has also been widely awarded and recognized, including receiving the 2015 Artist in Residency Grant from the Asian Cultural Council in New York City and a 2016 COLA Individual Artist’s Fellowship from the Department of Cultural Affairs from the City of Los Angeles. Her work has been featured in books like “Loaded: Guns in Contemporary Art” by Suzanne Ramljak; “Sex Pot: Eroticism in Ceramics” by Paul Mathieu; “Contemporary Ceramics” by Susan Peterson; “Color and Fire: Defining Moments in Studio Ceramics, 1950–2000” by Jo Lauria; and “Postmodern Ceramics” by Mark Del Vecchio. She has also been featured in numerous magazines and news articles, including in Art Ltd., Ceramic Arts and Perception, American Ceramics, Los Angeles Times, and the HuffPost. Her most recent artist profile was in “Psychological Perspectives” by Nancy Mozur.

Mark Steven Greenfield

A native Angeleno, Mark Steven Greenfield studied under Charles White and John Riddle at Otis Art Institute in a program sponsored by the Golden State Life Insurance Company. He went on to receive his Bachelors degree in Art Education in 1973 from California State University, Long Beach. To support his ability to make his art, he held various positions as a visual display artist, a park director, a graphic design instructor and a police artist before returning to school, graduating with Master of Fine Arts degree in painting and drawing from California State University, Los Angeles in 1987. From 1993 through 2010 he was an arts administrator for the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; first as the director of the Watts Towers Arts Center and the Towers of Simon Rodia and later as the director of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. In 1998 he served as the Head of the U. S. delegation to the World Cup Cultural Festival in Paris, France and in 2002 he was part of the Getty Visiting Scholars program. He has served on the boards of the Downtown Arts Development Association, the Korean American Museum, and The Armory Center for the Arts, was past president of the Los Angeles Art Association/Gallery 825 and currently serves on the board of Side Street Projects.

Greenfield’s work has been exhibited extensively throughout the United States most notably at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, the Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art and the California African American Museum. Internationally he has exhibited in Thailand at the Chiang Mai Art Museum, in Naples, Italy at Art 1307, Villa Donato, the Gang Dong Art Center in Seoul, South Korea and the Blue Roof Museum in Chengdu, PRC. He is represented by the Ricco Maresca Gallery in New York and the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica, California. His work deals primarily with the African American experience and in recent years has focused on the effects of stereotypes on American culture stimulating much-needed and long overdue dialog on issues of race. He is a recipient of the L.A. Artcore Crystal Award (2006) Los Angeles Artist Laboratory Fellowship Grant (2011), the City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellowship (COLA 2012), The California Community Foundation Artist Fellowship (2012) the Instituto Sacatar Artist Residency in Salvador, Brazil (2013) and the McColl Center for Art + Innovation Residency in 2016. He was a visiting professor at the California Institute of the Arts in 2013, and was an artist-in-residence at California State University, Los Angeles in 2016. He currently teaches at Los Angeles City College.

Bryan Ida

Ida was born and raised in Palo Alto, California, and as a child, grew up playing music and participating in youth symphony and band. His friends while growing up were the sons of a gallery owner named Paula Kirkeby who owned a fine art press and gallery named Smith Andersen. Through my friendship with this family, Ida was exposed to the small but important art world of Palo Alto in the 70s and 80s. Kirkeby was in many ways the world around which the peninsula art scene rotated. Being based in Palo Alto she worked with many faculty at Stanford and other bay area institutions and she represented many luminary artists such as Sam Francis, Bruce Conner, Nathan Oliveira, Frank Lobdell, and Joe Zirker. Ida didn’t know it at the time but meeting these people in this informal setting would have a great influence on him and on the direction of my life.

He has always had a need to express himself in a uniquely creative manner and in his youth his outlet was music. This passion led to studying electronic music composition and computer sound design in college.

After college in 1988, Ida went to work for Sam Francis, the noted Abstract Expressionist painter, as his studio assistant. Prior to working for him, Ida had known Sam for many years through his connection with Paula. In his Palo Alto studio, Francis was painting a large commission for the new United Government building in Bonn, Germany. The painting was approximately 20 x 40 ft. —a very large mural. Ida recollects, “I felt privileged to be in the studio while Sam worked. I vividly recall helping him with buckets of paint and painting tools, taking photographs, and archiving this period. Working side by side with Sam, I had the opportunity to absorb some of his knowledge and to instinctively understand his perspective and we would often talk about the correlation between music and painting and how it is the expression of the same consciousness but is conveyed through different senses.”

In the early 90s, Sam moved him down to Los Angeles into his big studio in Venice and Francis would be instrumental in the change of Ida’s artistic expression from music to painting. In working closely with Francis, Ida realized that the ‘artistic language’ that was most natural to him was ‘the visual.’ Ida found that he had the ability to put together visual thoughts and phrases much easier than with music. Through Francis’ generosity, Ida was given the opportunity to paint in his Venice studio that he no longer used, and in doing so started his lifelong journey into visual arts.

In the past 30 years, Ida has shown extensively in Europe, the U.S., and Asia. He is represented in Los Angeles at the George Billis Gallery, and in Taiwan and Singapore at Bluerider Art.

Walterio Iraheta

Walterio Iraheta studied Applied Arts at Centro Nacional de Artes, CENAR and the University Dr. José Matías Delgado in El Salvador, the country where he was born; Graphic Arts at the Chicago Cultural Center, in the US, and then at School of Visual Arts, La Esmeralda, México. He has won the first place in the Art Biennial Paiz of El Salvador 2007; an Honorable Mention in the competition of Contemporary Art in Palma de Mallorca, Spain 2004; first prize in the Contemporary Art Biennial of Central America, 1998, among others. He has had more than 35 solo exhibitions and has participated in over 150 group shows like the Photography Biennial in Lima, Perú 2012; the Venice Biennial, Italy 2011; Pontevedra Biennial in Galicia, Spain 2010; The X Havana Biennial, Cuba 2009; The Latin American video projects Visionaries at The Itaú Cultural Sao Paulo, Brazil and The Museum of Contemporary Art Reina Sofia, Madrid, 2009; Valencia-São Paulo Biennial, Spain 2008, among others. In the last ten years he has combined his artistic work with those of curator and cultural management, coordinating projects like The National Drawing show and Photography Festival ESFOTO in his country. He lives and works in San Salvador, El Salvador.

Iraheta has gone through a process which began with traditional techniques, but continuously expanded to include any technique or material in the creation of artworks. As a creator, he is constantly moving towards new languages and topics, passing from one to another without losing his way in the search for aesthetic results. At times, however, his choices come dangerously (and consciously) close to being too kitschy, or he seems unnecessarily reticent to breaking with convention, in an effort to preserve a traditional sense of visual structure, and the sort of perfectionism and appreciation for detail that has characterized him as a draftsman.

What remains unchanged is the direct and enriching conversation Iraheta achieves between his work and its viewers. There are moments of mockery and humor, or of social consciousness, as well as more intimate passages related to love and memory. Currently, he is very interested in issues related to human movement, the phenomenon of migration and hybrid cultures, and in mixtures of values and traditions among people of different regions. In some pieces, the focus is on himself as the subject, a natural consequence of the self-referentiality apparent in all his oeuvres.

Tracy Keza

Raised in South Africa and Rwanda, Tracy Keza is a Kenyan-born, multi-continental-based photographer and an undergraduate student at Trinity College. When Keza moved to the US for her undergraduate career, she found herself having to integrate into the African American/Black culture at a time where racial tension and injustice towards Black and Brown people has become the norm due to the socio-political systematic bias that perpetuates racial inequality. As a visual artist, she finds herself in a unique position that allows her to explore and dissect issues of race, religion, gender, and diasporic identity from different perspectives.

She completed her pursuit of a dual major in both Environmental Science and Photography and returned to Africa with the power of both science and art to create social change. In January 2016, Keza was selected as the artist-in-residence for Studio Revolt, an award-winning collaborative media lab currently engaged in international collaborative work. Her photography-based project Hijabs and Hoodies was incubated with Studio Revolt during her 2016 residency and has since traveled to several parts of the US.

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew’s photo-based artwork is often a striking blend of still and moving imagery. Her work draws on archival photographs as a source of inspiration to re-examine historical narratives and colonization’s legacies.

Matthew’s recent solo exhibitions include the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada, Nuit Blanche Toronto, and sepiaEYE, New York. Matthew has also exhibited her work at the RISD Museum, Newark Art Museum, Museum of Fine Art, Boston, San Jose Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts in Texas, Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the 2018 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2018 Fotofest Biennial, 2009 Guangzhou Photo Biennial, as well as at the Smithsonian Institution in 2016.

Grants and fellowships that have supported her work include a MacColl Johnson, John Guttman, two Fulbright Fellowships, and grants from the Rhode Island State Council of the Arts. In addition, she has been an artist in residence at Yaddo and MacDowell.

Matthew is a Professor of Art at the University of Rhode Island and was the Director of the Center for the Humanities from 2013-2019, and the 2015-17 Silvia-Chandley Professor of Nonviolence and Peace Studies and is represented by sepiaEYE, New York City.

Images (top to bottom):Photo of Mariona Barkus: Photo courtesy of the artist, Photo of Chess Brodnick: Photo courtesyt of the artist, Photo of Claudia Casarino: Photo credit by Javier Medina, Photo of Gerald Clarke: Photo credit by Palm Springs Life, Photo of Keiko Fukazawa: Photo credit by William Short, Photo of Mark Steven Greenfield: Photo credit by Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Photo of Bryan Ida: Photo courtesy of the artist, Photo of Walterio Iraheta: Photo credit by coleccion SOLO, Photo of Tracy Keza: Photo credit by Hijabs and Hoodies Website, Photo of Annu Palakunnathu Matthew: Photo credit by by David Wells

Mariona Barkus

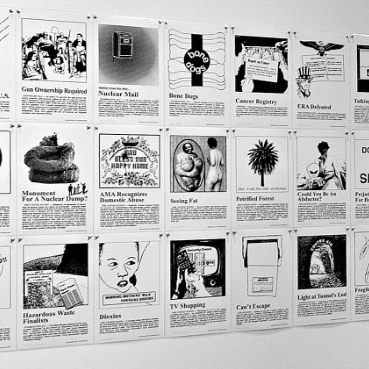

For Mariona Barkus, it all started at an early age —reading the newspaper, listening to the news on the radio or TV, and arguing with her conservative Republican father— which fostered her nascent political awareness.For the last forty years, through the Illustrated History collection and installation, Barkus has been a chronicler of these times in our lives, being a witness, offering testimony and documentation, seeking to expose, inform, enlighten, reveal, and inspire. All with a dash of wry humor—if at all possible. The stories are true, compilations of texts from newspapers and other sources, with interpolations by Barkus. Over the years, the images have incorporated collage, photography, and painting. Each of these 138 Illustrated History broadsides asks the viewer to linger, read, and contemplate its message. While reading, Barkus wants the viewer to note the different years that each of the Illustrated History panels was created, and to perhaps notice that many of the issues important years ago are still quite relevant today.

Additionally, over 90,000 metric tons of nuclear waste are stored above ground at 121 sites in 35 states of the United States. Around 1995, Yucca Mountain, Nevada was chosen as the ideal place to bury this long-lived radioactive waste. Barkus was inspired by the call for a system of surface markers to warn of this planned lethal underground cache. She thought about the ideal surface marker to ward off intruders for future millennia. In communicating so far into the future, most could assume that despite the passage of time, and with evolving cultures and languages over time, future beings will still have the same basic human bodily functions —thus, comes the inception of Barkus’s installation titled Monument For A Nuclear Dump. The logical next step for her was to provide a roll of “toilet paper” that encapsulates an ‘archive’ of newspaper clippings referencing nuclear waste over the last four decades, in order to mimic the folly of this entombment, while simultaneously documenting ubiquitous nuclear waste proliferation. This continues to be a work in progress that will continually grow over time, as nuclear waste continues to proliferate over time.

While environmental activists have successfully kept Yucca Mountain from being activated, New Mexico has the only active below-ground nuclear waste dump, which will be full and sealed soon. The illustration in Our Lethal Legacy presents some of the texts suggested by the Sandia Report which suggested written warnings as well as physical barriers to keep civilizations, millennia in the future, away from this highly radioactive and lethal repository.

In her newest installation, created for this exhibition, titled Mad As Hell and Not Taking It Anymore, these metallic ‘critters’ marching forth in formation, are out to battle with malevolent misogynist forces. A vengeful army taking back the right to women’s physical autonomy and expressing the anger felt by generations of women subjected to sexual harassment and violence. Barkus has shown her work in solo and group exhibitions throughout the United States as well as internationally in Ireland, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, and Spain, and is in the collections of the Yale University Art Museum, Getty Research Institute, Art Institute of Chicago, Franklin Furnace Collection at the Museum of Modern Art, Special Collections at the Whitney Museum of Art, Center for the Study of Political Graphics, Long Beach Museum of Art, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Lucy Lippard Collection at the New Mexico Museum of Art, UCLA, Indiana-Purdue University,among many others.

A clenched fist atop a vaginal speculum becomes the embodiment of women’s rage at being devalued, denied education and income equality, considered second-class citizens, and subjected to violence just because they are women. Expose egregious sexual harassers and predators, add in outrage at state legislatures restricting women’s equality, health care, and reproductive rights, mix in fury at the day-to-day sexual harassments, assaults, and discrimination seared into many women’s memories, and voila, viewers have the sentiments expressed by Mad As Hell and Not Taking It Anymore.

Her work has been reviewed in numerous catalogs and periodicals including: The Los Angeles Times and Artweek, among others. Some of the books featuring her work are Crossing Over: Feminism and Art of Social Concern by Arlene Raven; Other Visions, Other Voices by Paul Von Blum with a forward by Lucy Lippard; Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook by The Visual Studies Workshop; From Site to Vision: The Woman’s Building in Contemporary Culture, edited by Sondra Hale and Terry Wolverton, and most recently, from the University of California Press: American Artists Against War 1935—2010 by David McCarthy. Barkus has received grants from the City of Los Angeles, Women’s Studio Workshop, and New York State Arts Council.

Mariona Barkus

Illustrated History, 1981-2020

installation of the collection in its entirety

138 laminated electrostatic prints

Courtesy of the artist

Mariona Barkus

Monument for a Nuclear Dump,

1988-2020

mixed media installation: two framed digital prints and “toilet paper roll” of glassine encapsulated nuclear waste newspaper clippings

Courtesy of the artist

Mariona Barkus

Mad As Hell and Not Taking It Anymore, 2020

mixed media installation: 78 fist/speculum sculptures which are mixed media: silver paint on paper clay fists and plastic vaginal speculums on plexi bases

Courtesy of the artist

Chess Brodnick

Chess Brodnick’s current work focuses on portraiture and painting. A realist portrayal of faces and figures that are a dynamic representation of life. The artist’s psychological images emerge in startling and provocative ways, unfolding profound internal and external emotion onto the picture plane.

Faces are what interests him most as an artist. To him, it is the most expressive and defining part of a person, and is ripe for creative expression. By illustrating the human face, the artist makes portraits of “events”: the emotional, physical, psychological impact of various events from his own life, in hopes others can relate, and connect to their own emotional and mental states of mind. He uses realism combined with abstraction to illuminate the results of an “event”. This is done by distorting a face and placing it in an abstract field— much like in Cubist works —thereby showing the outside and inside of a person, simultaneously, in response to an occurrence. The resulting image is a more dynamic and accurate portrait of what we each experience in our lives.

The drawings included in this exhibition are part of a series of self-portraits representing the artist’s response to events in his life over the last two years of the pandemic, and the social and political unrest that has also plagued the US, and the world, during these times. The paintings portray a combination of “my inner and outer reactions simultaneously. The abstract “field” reflects my thoughts and emotions to a specific event as though they were transformed and projected outside of my head.” The face is at times “fractured”, or abbreviated, to show the impact of the event as it occurs in time. Life is not linear, and through his art, he finds the perfect way to capture this fact.

His drawings strive to present transparent distillations of life experience and inner emotional turmoil. Faces bend, contort, and segment, as life would move them. The external and internal forces that shape a life in a moment come to coalesce, pushing and pulling as if to say, “See me, see it all” — good, or bad.

“To my mind, purely expressive forms of art, poetic perhaps, often spring from the media of ink painting, charcoal, and dark pencil drawings.” The artist postures from the extreme of utter dark to the lightest of light, making stops in the grey of uncertainty. There is no concealing, no reliance on color, to refine ideas and emotion— just light and shadow, shape and truth.

Chess Brodnick

The inner limit, 2020

Sumi-e ink painting on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Chess Brodnick

It begins at love, 2020

Sumi-e ink painting on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Chess Brodnick

Absolved for the day, 2020

Sumi-e ink painting on paper

Courtesy of the artist

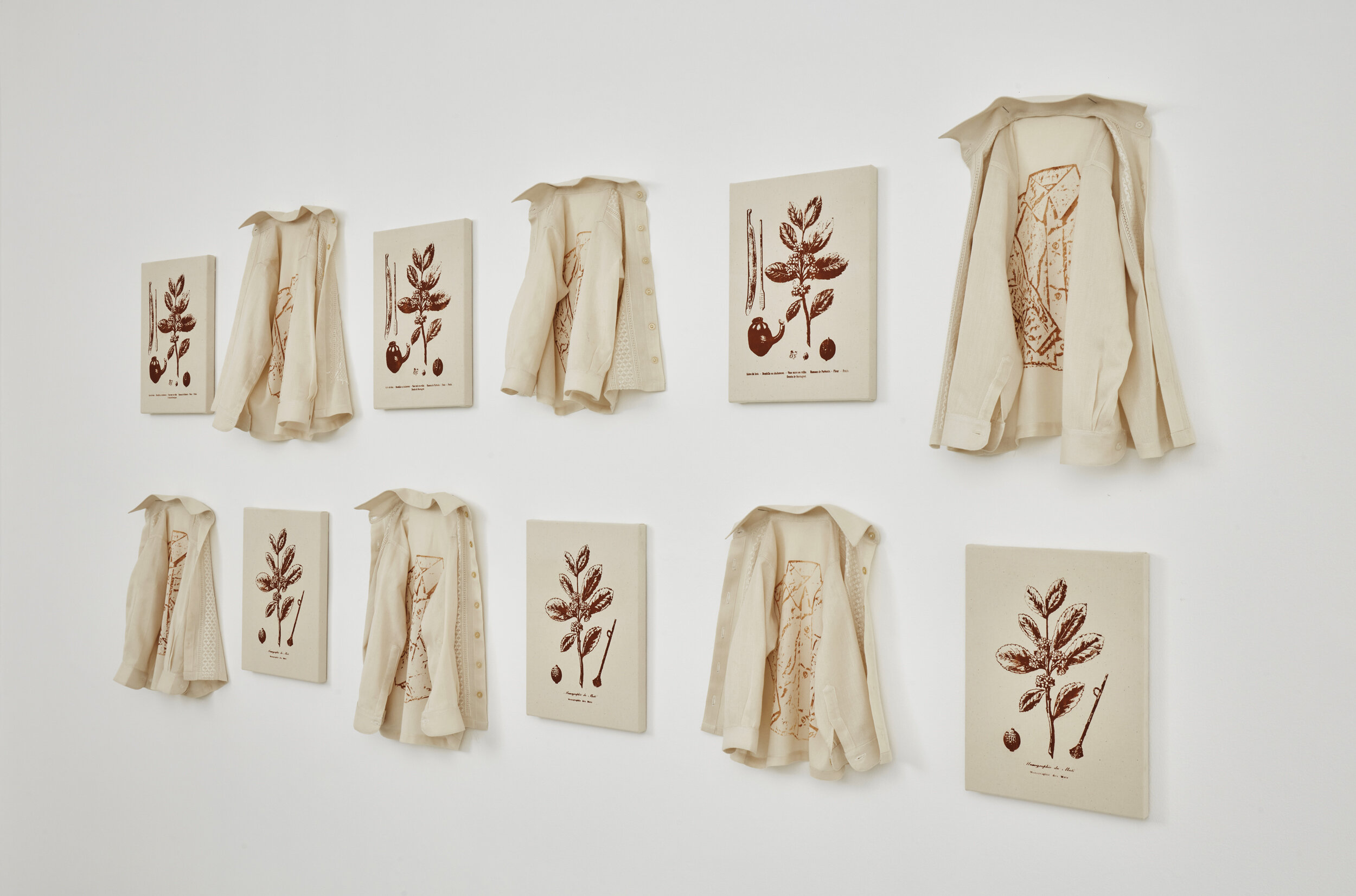

Claudia Casarino

Claudia Casarino, Paraguayan by birth, demonstrates through her work, the importance of the “body as territory”, addresses the key role of women in society, and our indelible origins as humans. Spanish Colonization, the Hispano-Guaraní pact, and the War of the Triple Alliance against Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, are a series of historical events irreversibly linked to both the “silenced” and “silent work” of the women of Paraguay —indigenous or otherwise. Casarino’s body of work represents inerasable living reflections of the mind—through collective memory; clothing—by dress and cultural tradition; and skin or blood—human traces representing mankind—and more specifically, the Paraguayan struggle. These three elements, conceptually bridged with the use of the fiery, brownish-red, iron-rich earth of Paraguay (known also to exist throughout many regions of South America) as pigment in her work, conveys the struggle that plagues its peoples, through a shared history of conquest and colonization, with the exploitation of the indigenous worker, land loss, and centuries of economic and socio-political setbacks.

Casarino’s artworks most often and specifically deal with subjects surrounding gender issues, canons of beauty, the roles imposed on women, and those that women impose on themselves. These explorations are frequently intertwined with the female body and its relationship with clothes. Her work showcases her personal history, which she transmits through her own body, guiding it into a societal dimension. In her Inhabited Dresses series, Ellas 5 (trans. She 5, the plural for “5 females”) is a hanging arrangement of five white cotton dresses doused in red earth, as though the women presumably wearing them had been toiling in the wet earth, staining only the lower-thirds, while the top two-thirds remain pristine and pure. In doing so, the artist reveals a political discourse about the place that women have in Paraguayan society. A political reflection on the presence of women from generation to generation, and their bodies, in a state of tension. Casarino shows us how each historical event lived in Paraguay, including colonization and war, dictatorship and economic injustice, conjoins the “silenced”, and quite “traditional work” of women. In traditional Indigenous and European fashion, handsewn clothing, crocheted lace and dressmaking is passed down from generation to generation as “women’s work”. And by soiling them with red-brown earth, she alludes to the fieldwork that has become part of the agricultural labors of all indigenous workers, including women, and children.

In Indelible, Casarino squares crisp white linen, embroidered shirts side-by-side with silkscreen images of yerba mate plants. The shirts are made with aopo’i, a lightweight cotton fabric that embodies the textile culture of Paraguay since pre-colonial times. The shirts and prints are stained, marked, with red-brown earth from the Paraná River, dissolved in water. The ancient Guaraní had said that the red of the land comes from indigenous bloodshed during the violent conquest of their territories. But that color also comes from the same spilled by the mensú (meaning “monthly” but referring to the farm laborer, someone who works on a monthly basis), and the tareferos who, in the same region, collect yerba mate leaves in extreme and exploitive conditions: grueling labor for low wages, under unsafe, unregulated circumstances, in remote areas, far from home and family. These conditions, typical of slavery, cause injury and often death to these workers. The artwork is based on the writings of late-19th century author Rafael Barret (of British-Spanish descent) in El dolor paraguayo (The Paraguayan Pain) Photo Credit: Javier Medinawherein the mensú are described as arriving to work with no more than their own shirts on their backs —made by their wives or mothers— which were so treasured, that they preferred to expose the skin of their backs, tear their flesh by the crackling and heavy loads carried, rather than to destroy their revered delicately handmade garments. Mensú shirts were worn backward to cover the chest and expose the back. The garments exhibited by Casarino bear earthly, blood traces of other drawn shirts that seek to replace the part subtracted from the back of the worker —seeking somehow to reverse the tragedy. These, alongside earth/blood-painted images of the yerba mate plant, complete the work. Yerba mate is considered a “traditional staple” of the South American breakfast, afternoon teatimes, and sometimes imbibed throughout the average day, all around most of South America. Its consumption, per capita, is highest in Uruguay, followed by Argentina, then Paraguay, and Brazil.

Casarino works from the conceptual point-of-view, reflecting on female gender issues, women’s work traditions, the impacts of poverty and the exploitation of natural and human resources, and the consciousness of the body affected by borders and forced transits. Her work deals with interpreting the universe of women as a subject of social transformation.

Claudia Casarino

Ellas 5, 2019

Cotton dresses with red earth

Variable dimensions

Edition of 1

Courtesy of RoFa Projects Gallery

Claudia Casarino

Pynandi (ni puta, ni diosa, ni reina)Barefoot (not a whore, neither a goddess, nor a queen), 2010

Cotton dresses

Edition of 1

Courtesy of RoFa Projects Gallery

Claudia Casarino

Indelible / Indelible, 2010

Serigraphs of colored earth

on canvas and ao po’i shirts

Edition of 5

Courtesy of artist and RoFa Projects

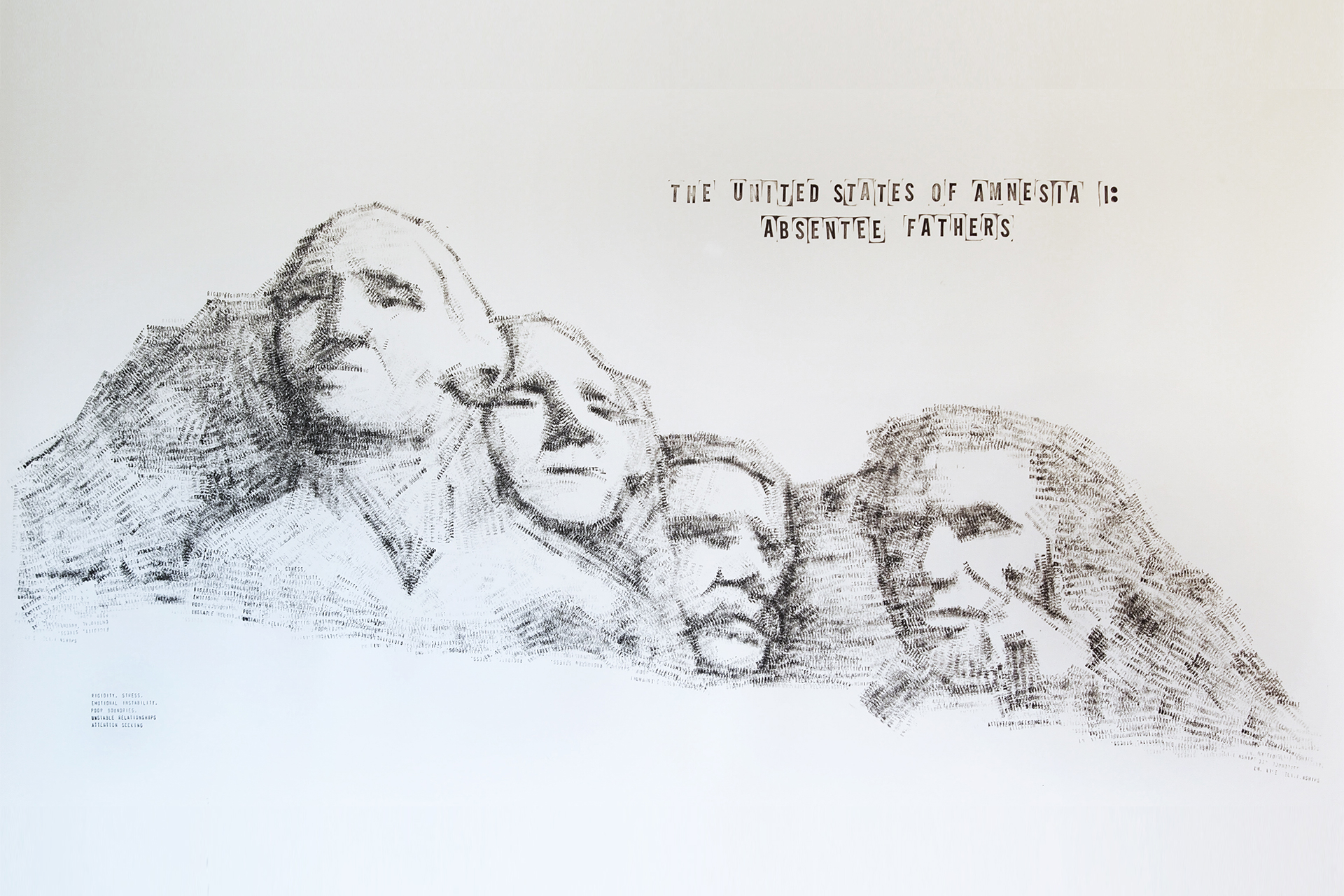

Gerald Clarke

Gerald Clarke has consistently chosen to not have a singular approach to his work: he chooses whatever media, format, or action that he believes would best express the idea, emotion, or concept he is exploring. Clarke also recognizes his need for meaning. While he has a deep appreciation for the aesthetic object, and genuinely enjoys the physicality and craft of making an art object, his ultimate goal as an artist is for his work to have a meaningful interaction with the viewer. In hindsight, Clarke recognizes how his perspective of the viewer has evolved. Early in his career, and as a member of the Cahuilla tribe, Clarke sought to educate the non-Native viewer about contemporary Native culture. Over time, Clarke came to two realizations regarding his work and the viewer: first, by focusing his efforts to educate the non-native viewer, Clarke neglected his own tribal community; second, the more personal, and honest, Clarke is with his own work, the more universal it becomes.

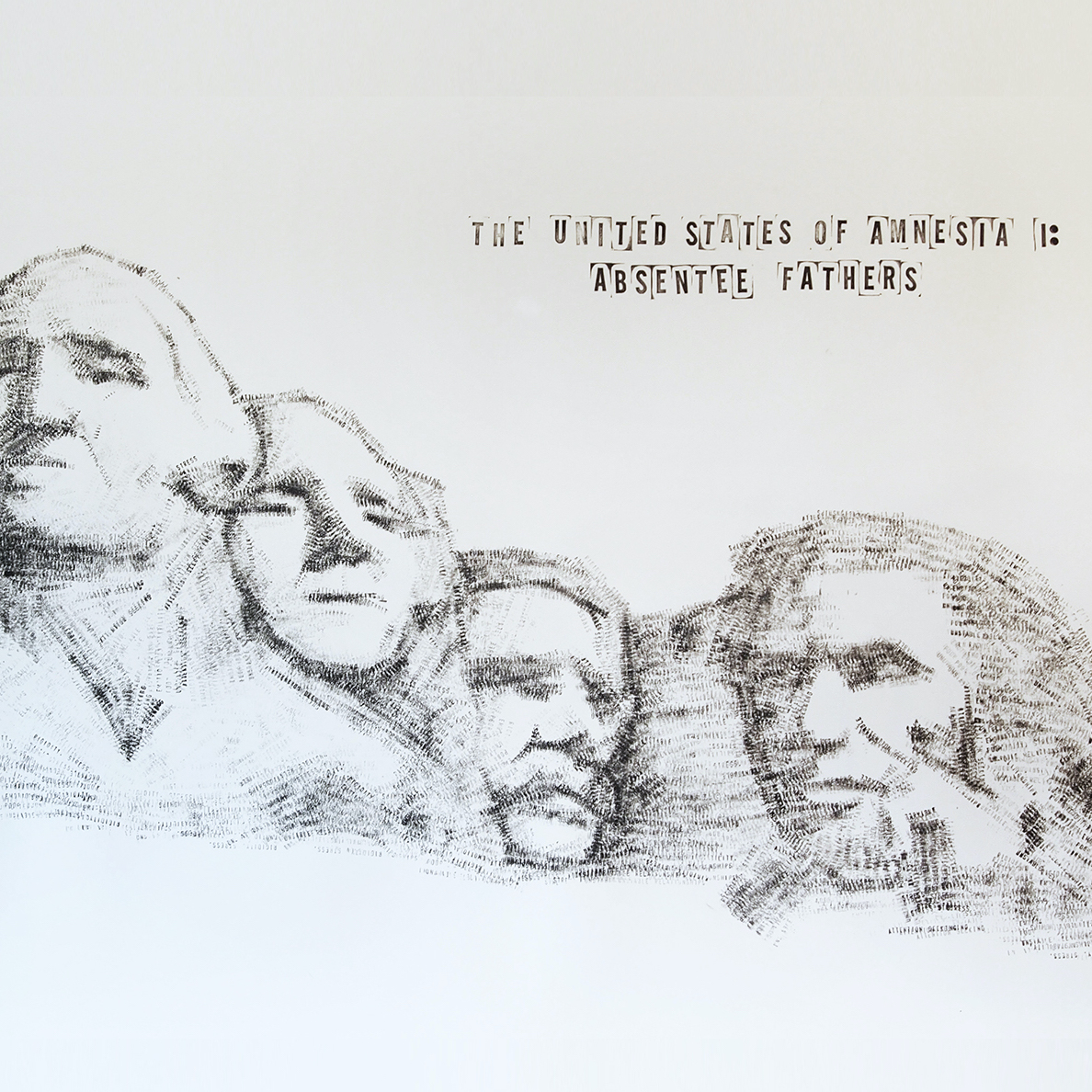

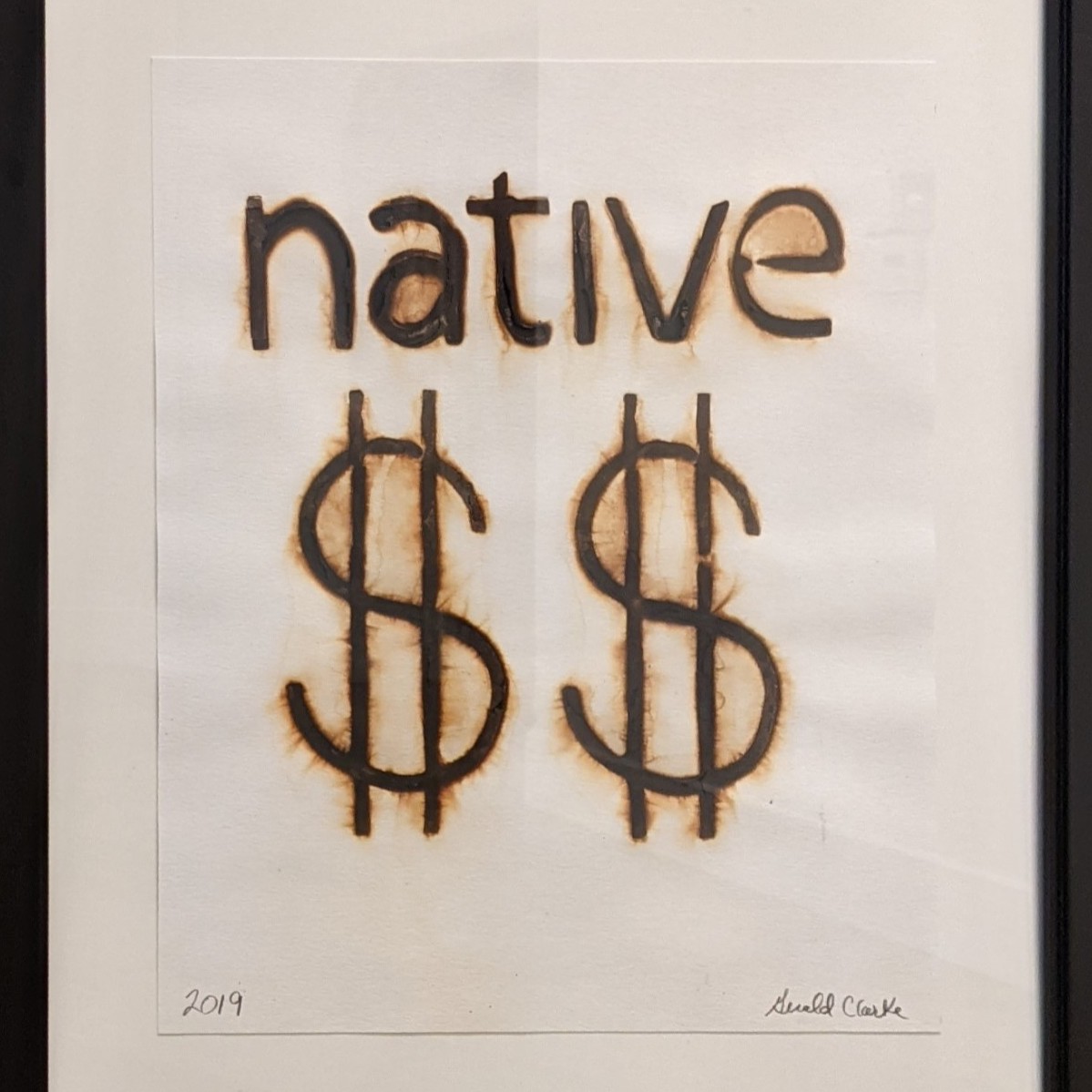

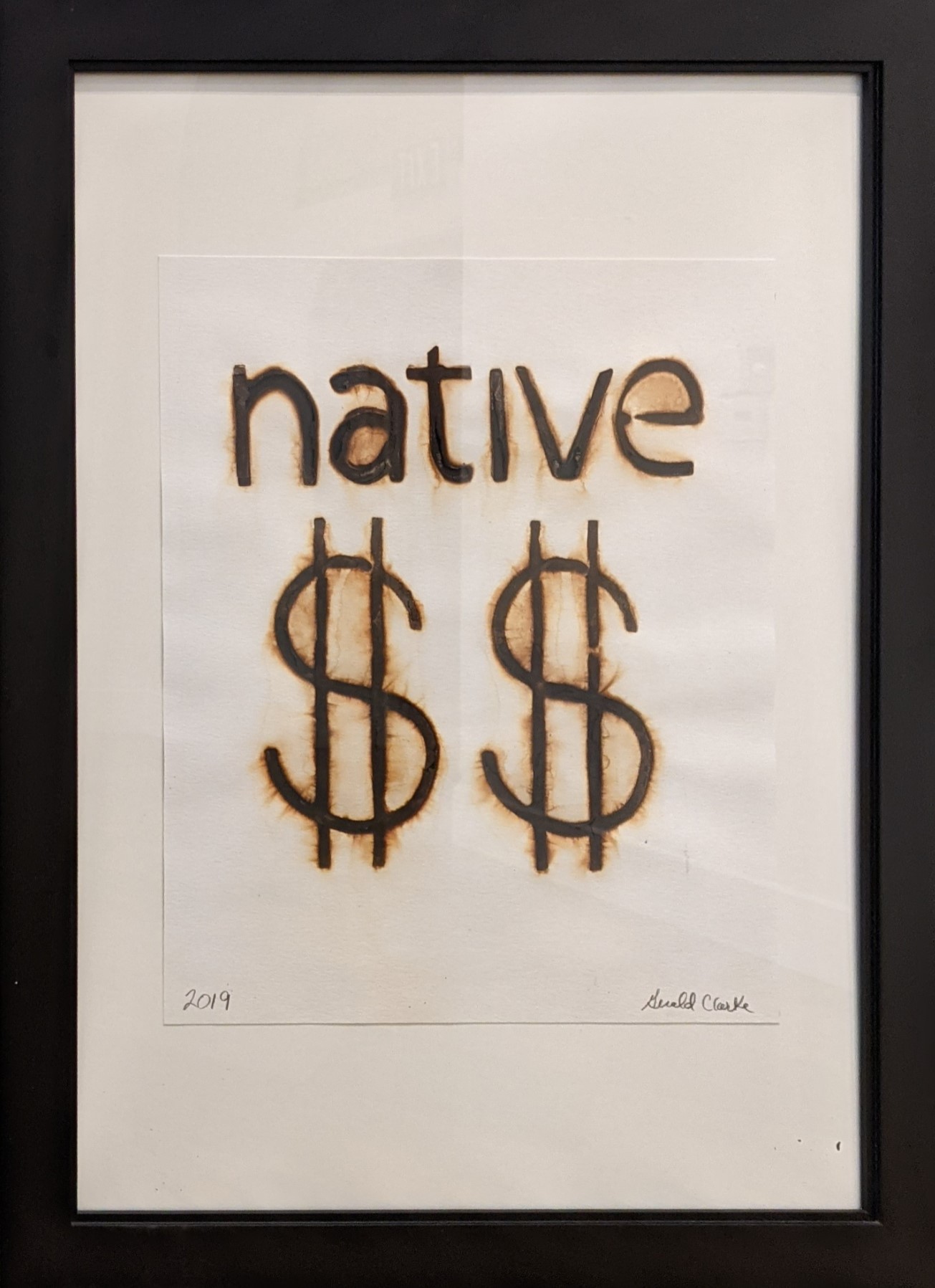

The work exhibited includes work from both his Branded Prints and his Stamped Prints series. In both cases, he uses unique and inventive methods to create one-of-a-kind prints on paper. In 2002, the first work ever made for the Branded series involved constructing a branding iron out of metal with a word spelled out in all caps: INDIAN. This required blacksmithing and fusing several pieces of metal together into a forging iron that, in itself, is its own piece of sculpture. This branding iron is currently in the collection of the Autry Museum in Los Angeles.

Reminiscent of property ownership, the branding iron, in itself, is also evocative of a tool of the “Old West” and even more painful reminder of the use of fire and metal to burn hide or skin, animal or human. In the work Native Inverted, Clark chars multiple “burns” onto wet watercolor paper with his all-lower-case “native”-worded branding iron. Each print reveals a unique imprint due to several factors: the heat of branding iron, the dampness of paper, and the length of burn. The artist repeats the technique, but with varying degrees, revealing slightly different, but purposeful, effects. He goes a step further, by amalgamating, mixing, or singling-out, new words with the word “native”, like “Art”, “Amnesia”, and sometimes juxtaposing these words with “Immigrant”, dollar signs, and/or a brownish “smoldering” map of the continental US.

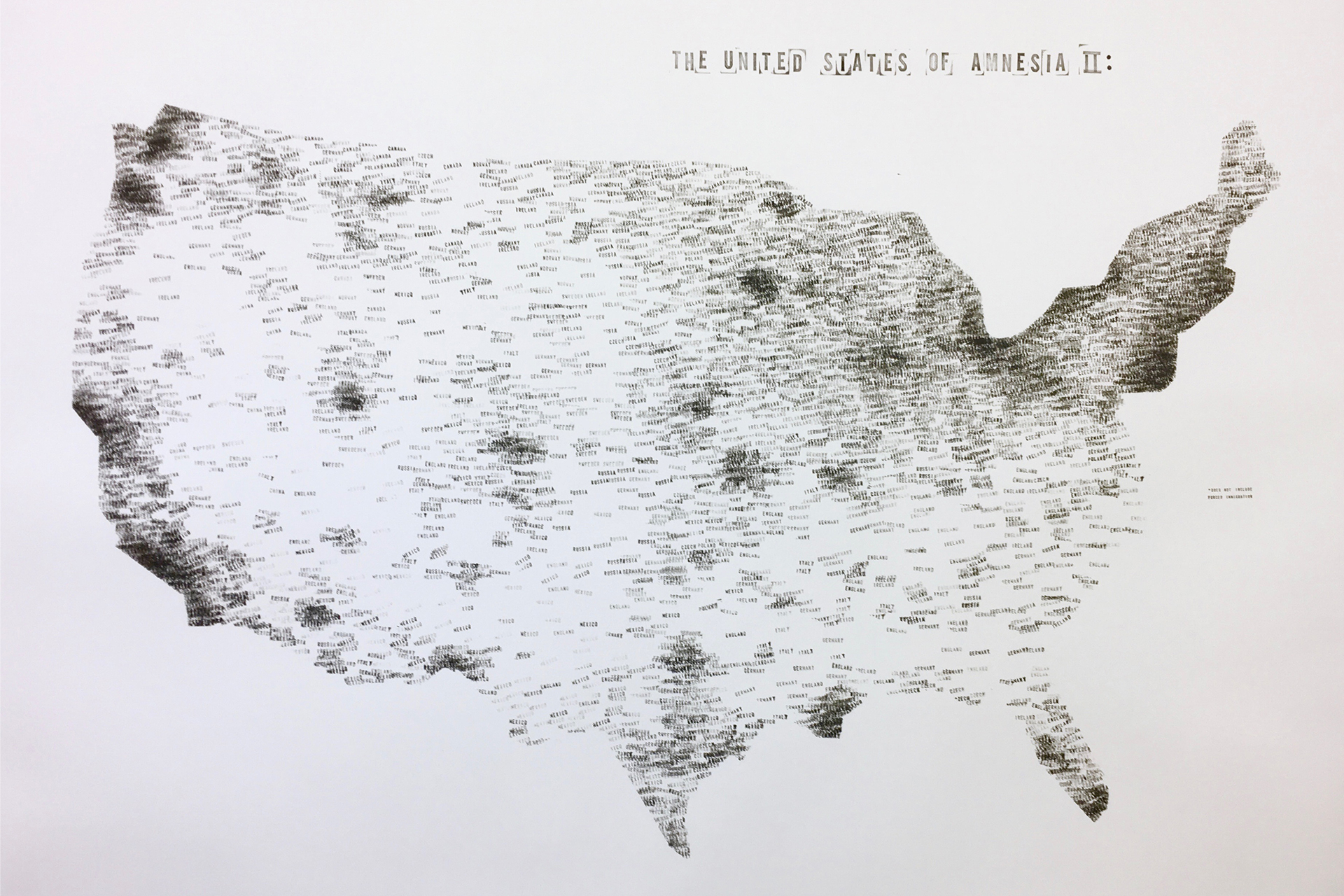

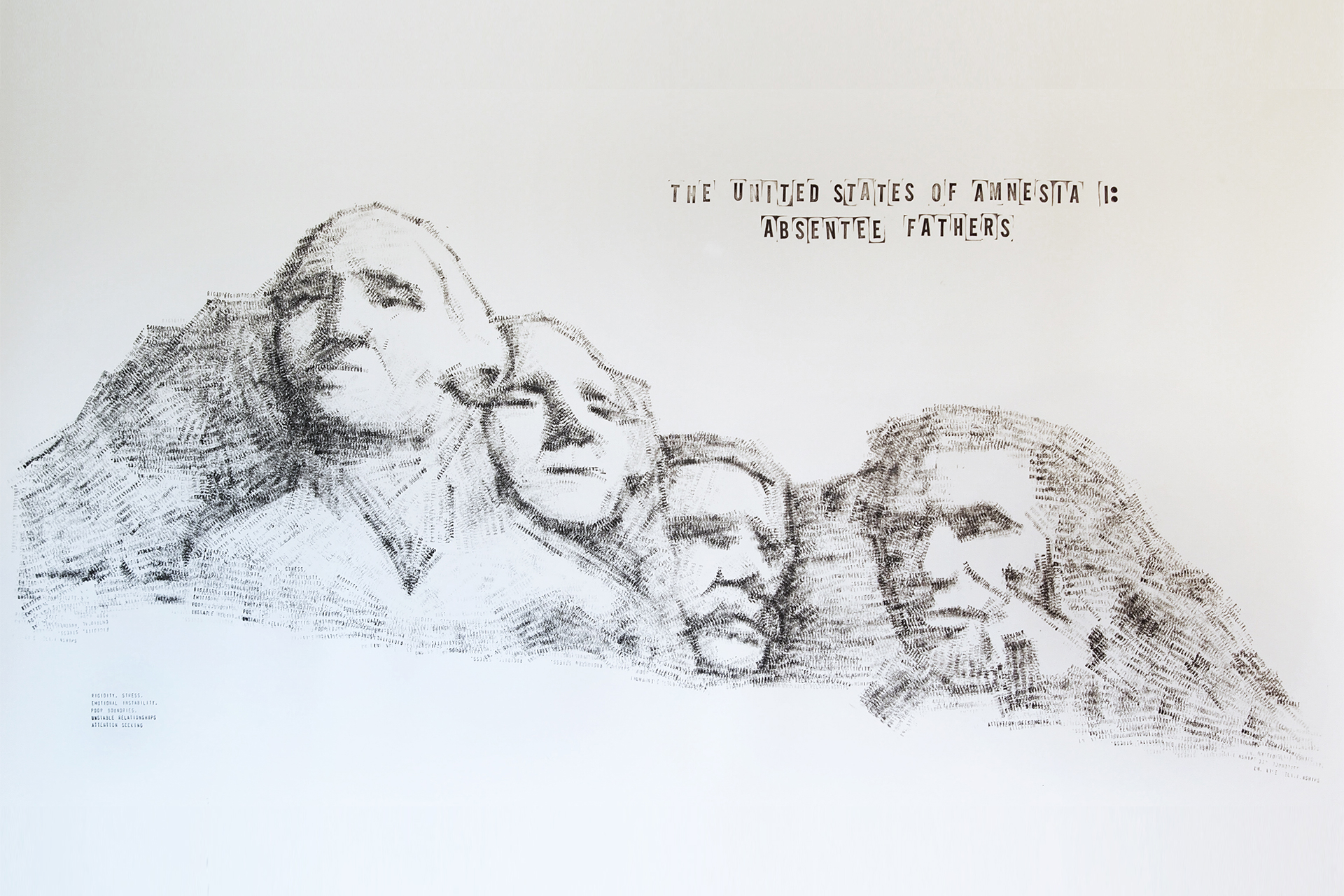

Using another “neo-printmaking” technique, the Stamped series is created by using immigration data and maps from the Internet, in combination with rubber stamps. Clarke starts by projecting maps representing US immigration settlement patterns onto his paper, and then stamping the names of the countries of immigrant origin onto the paper using a rubber stamp. The maps used purposefully do not include forced immigration (i.e., migration by slavery, ethnic re-location). England, Germany, Ireland, Poland, and Russia permeate the map, just to name a few emigrating peoples. Each work takes about six hours to complete, and the “map” simply reveals itself over time. The current immigration debate puzzles Clarke: “Unless you are a Native Indigenous American, you come to the US from immigrants.”

Clarke was raised with a traditional understanding of the world and the importance of family and community. He feels a responsibility to share his perspective and the humanity that everyone shares, and this is reflected in his work. He does not make Native American art. He expresses his Cahuilla perspective as a 21st Century citizen of the world with the passion, pain, and reverence he feels as a contemporary Cahuilla person. As a member of the Cahuilla tribe, he incorporates a variety of media to address issues of the recovery of Native American identity and its intersection with mainstream US culture and politics. Clarke’s work questions popular or ingrained views and offers alternative perspectives on contemporary issues and is offended by prejudice and inequality. He, instead, wants his work to appeal to any person who seeks understanding and acceptance.

Gerald Clarke

The United States of Amnesia II,

from the Stamped Prints series, 2017

Paper, ink, rubber stamp

Courtesy of the artist

Gerald Clarke

The United States of Amnesia II:

Absentee Fathers,

from the Stamped Prints series, 2017

Paper, ink, rubber stamp

Courtesy of the artist

Gerald Clarke

Native $$,

from the Branded Prints series, 2019

Charred watercolor paper

Courtesy of the artist

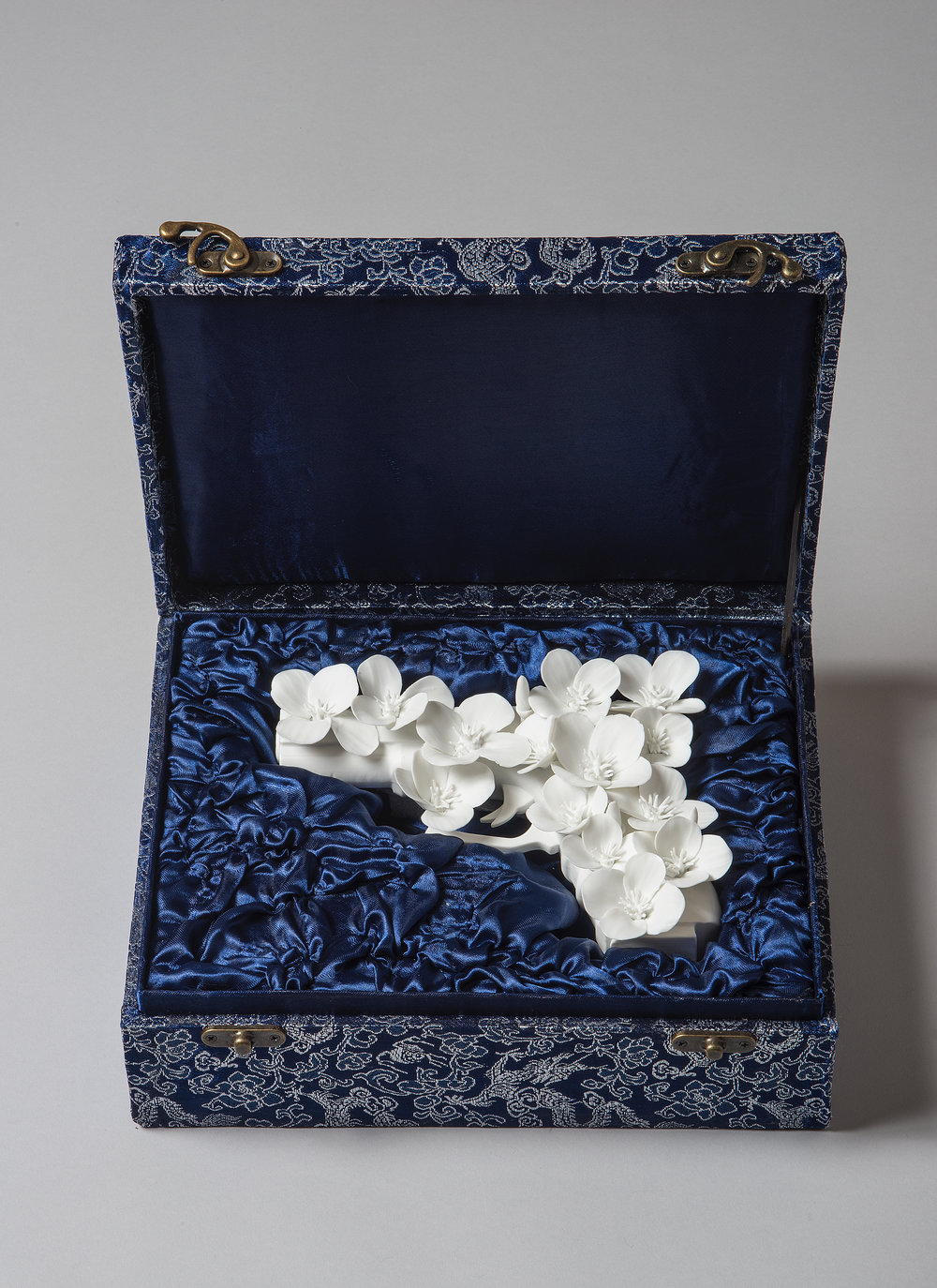

Keiko Fukazawa

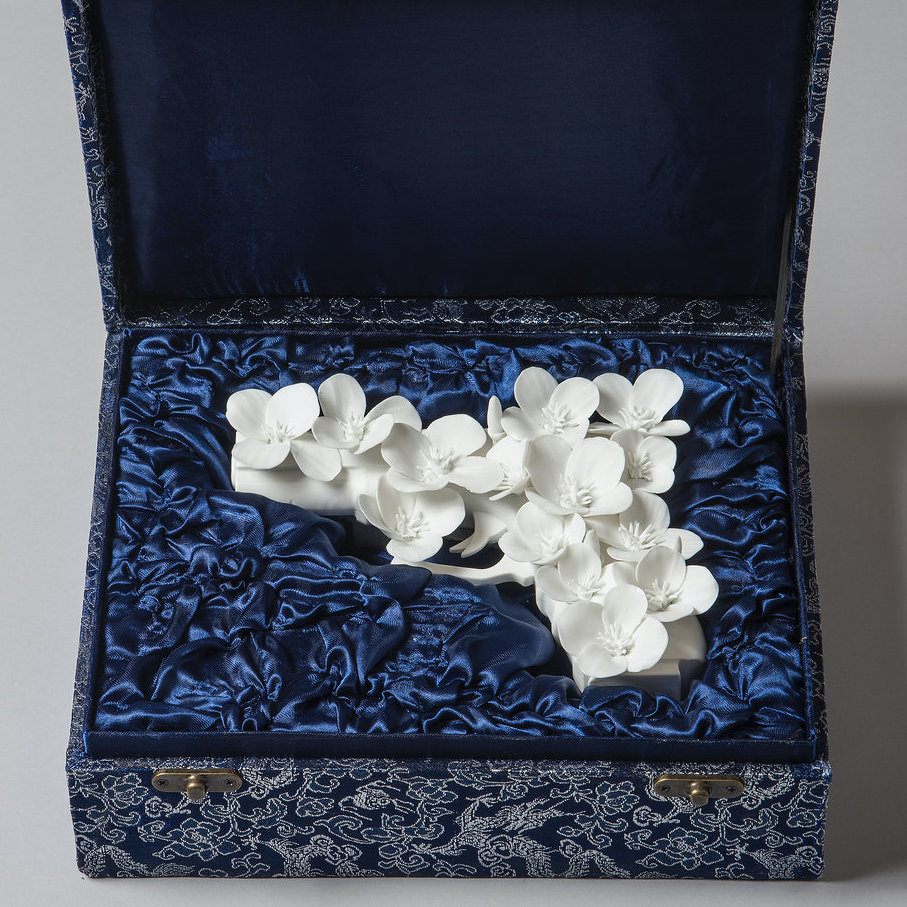

Keiko Fukazawa believes art should define its era and reflect what people are living through. Her recent work, and those exhibited in this show, engages with a devastating social, political, and cultural issue that affects millions of lives in America today.

Senseless massive deaths by firearms have skyrocketed in recent years, yet nothing has been done to systematically address this horrifying and pervasive issue. The country has been divided and immobilized under “all-or-nothing” debates for decades, and there will only be a win-win situation if we listen to each other, engage in healthy dialogue, and agree to act towards ending these terrible and preventable tragedies. However, politicians and the NRA are using this polarizing issue for their own gain, and their inability to progress beyond their own divisive greedocks efforts towards enacting lasting change.

From this context, Fukazawa has created a series titled Peacemaker as her first response to addressing America’s glaring gun culture and mass shooting problem. In white porcelain, she has recreated the most used handguns and rifles used in American mass shootings/gun violence from the past 20 years and covers them with the state flowers of where these shootings occurred. The color white represents the mournful state of mind of affected communities and symbolizes the purification of these hideous events. The flowers, which cover each weapon, remind us of life, instead of death.

Ironically, the name of this series, Peacemaker, is also the “colloquial” name of the infamous Colt .45, the most celebrated revolver in history, and an enduring symbol of the American West. The revolver was created in 1873 by American firearms inventor and manufacturer Samuel Colt, who was touted as “the Peacemaker,” for his work. The creation, proliferation, and romanticization of the Colt .45 revolver was the original model and impetus for all contemporary handguns used in contemporary shootings today.

Fukazawa’s most recent project is an installation piece on display called 48 Hours, which she intends to branch out from her Peacemaker portfolio. It is her first step towards creating subsequent installations to be titled 7 Days, and eventually into one monumental installation piece tentatively called 365 Days. Every day, about 100 Americans are killed with guns and hundreds more are shot and injured according to annual averages compiled by the Centers for Disease Control. This means over 36,500 Americans are killed with guns every year, including 2,812 children and teens killed or injured, annually. These staggering numbers and facts must be told as they are, especially in this time of “fake” news and contested truth.

365 days will eventually become one huge installation consisting of 36,500 porcelain guns, each labeled with a name of the victim, their age, and address where the violence occurred. The installation will change its form depending on the exhibition space with an effort to show the full impact of all 36,500 guns. Here, 48 Hours consists of 200 guns, reminding us of the number of people who die by gun violence every 2-day period in America.

Keiko Fukazawa

AKA AR-15-0416200732

(Blacksburg, Virginia),

from the Peacemaker series, 2018

Porcelain, Plexiglass Case

Courtesy of the artist

Keiko Fukazawa

Peacemaker 0214201817

(Parkland, Florida),

from the Peacemaker series, 2018

Porcelain, fabric box

Courtesy of the artist

Keiko Fukazawa

Peacemaker 1202201514

(San Bernardino, California),

from the Peacemaker series, 2018

Porcelain, fabric box

Courtesy of the artist

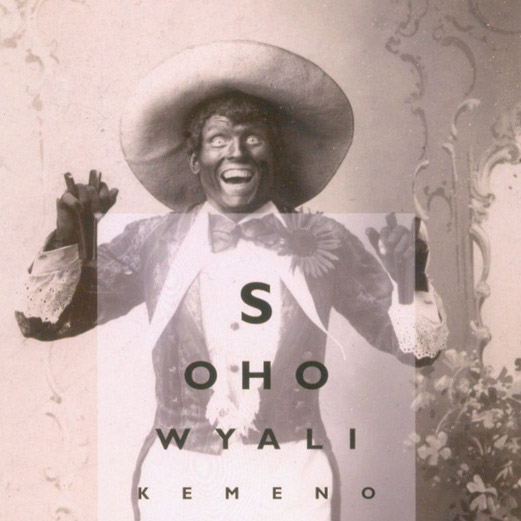

Mark Steven Greenfield

Mark Steven Greenfield’s work concerns itself with the complexities of the African American experience in contemporary society. The work often involves interpretation of the process by which images are formed in the subconscious. It is his contention that we borrow from the subliminal well on the conscious level and alternately navigate through various layers of consciousness to reach the source of our spiritual selves.

Greenfield’s initial exploration of this theoretical phenomenon was realized in work, which dealt with the psychological effect associated with African American stereotype as characterized by blackface minstrelsy and black cartoon characters from the 1930s and ‘40s. His scope has broadened to include explorations of dualities in contemporary society with references to African spiritual practices of the eguns (aka egguns, defined as the spirits of our ancestors, those related to us by blood and religious ties), and tropes (a figurative or metaphorical use of a word or expression) that make use of both positive, and negative energies.

In his Blackatcha series, Greenfield incorporates researched and appropriated images of white men in blackface posed in historical photos of blackface minstrelsy. This performative genre is known as a purely “indigenous American theatrical form that constituted a subgenre of the minstrel show. Intended as comic and sardonic entertainment, blackface minstrelsy was performed by a group of white minstrels (or traveling musicians) with black-painted faces, whose material caricatured the singing and dancing of slaves.” (Britannica.com) Even female figures are depicted by white males, dressed “in drag”, in order to ridicule and diminish both African American women, and homosexual men. “The form reached the pinnacle of its popularity between 1850 and 1870, when it enjoyed sizeable audiences in both the United States and Britain. Although blackface minstrelsy gradually disappeared from the professional theatres, and became purely a vehicle for amateurs, its influence endured in later entertainment genres and media, including vaudeville theatre, radio and television programs, and the world-music and motion picture industries of the 20th and 21st centuries.”(ibid) For obvious reasons, this form of “expression” has become, as it always was, a negative racist stereotype that represents the on-going bigotry and misogyny that continuously permeates American culture.

Super-imposed over the photographic images are what at first appear to be commonly used eye exam charts, also known as a “Snellen Chart” used to measure visual acuity. But upon closer look, the letterforms spell out poignant, explicit, and often jarring lyrics from modern-day popular Rap and Hip-hop songs from the likes of Trick Daddy, Sharissa, MC Eiht and DMX. In so doing, Greenfield’s prolific work from the early aughts causes us to ponder the layered quagmire of “the cause and consequence” of our historically shared past, its joint impact on all of us through its subsequent and current histories, as a result.

In turn, with 20/20 (or 2020) vision, his work today, just as it may have two decades ago, when created, makes us recognize the accountability and responsibility that is upon us to acknowledge and correct our past wrongs, as a nation, and a culture.

Mark Steven Greenfield

Problem Child, from the

Blackatcha series, 2001

Ink jet print

Courtesy of artist

Snell Chart Lettering:

“Mammy should have whooped yo ass”

Mark Steven Greenfield

Crazybones, from the

Blackatcha series, 2003

Ink jet print

Courtesy of artist

Snell Chart Lettering:

“So how ya like me now mutha fukkah”

Mark Steven Greenfield

Front, from the

Blackatcha series, 2002

Ink jet print

Courtesy of artist

Snell Chart Lettering:

“So whats yo punk ass thinkin bout”

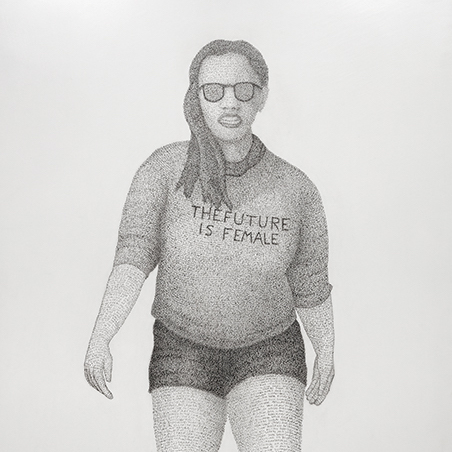

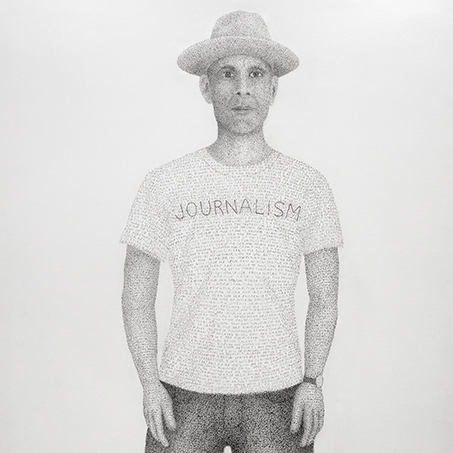

Bryan Ida

For the past five years, Bryan Ida has been engaged in a body of work that examines historic events in the context of the current social and political climate and raises awareness of past abuse and injustice by a government against historically targeted minority groups called con.Text.

Ida uses contemporary subjects with a connection to historic events to point out that man’s inhumanity toward man is universal and seemingly unending. The challenge is to express outrage to this injustice in a manner that can express as Ida states, “who I am and the way I want to communicate. I want to shout without screaming and inspire an emotional response from the viewer.” Emotions not of fear, hate and vengeance, but of compassion, respect, and a desire to right the wrongs that have been perpetrated on so many marginalized people in our society.

Ida uses people’s personal stories and then researches and references text from government documents, declarations, or other forms of institutional communication, and uses the words as his mark to render each person with the very words that affect them. Using the words as a building block in the formation of the image does not define the subject by the words being used, instead, the words are blended and blurred and are transformed from a label to a broader gesture that is used to define a new visual language of strength and beauty.

Ida chooses to represent America with no filter and depict how it is perceived today, but with reverence and respect for history and what brought us to this moment in time. Ida has always had a deep love of history and is intrigued by the fact that we do not always learn from history’s lessons and are constantly repeating past injustices.

His goal is for the work to be in a place where it can garner the most public interaction and contemplation. Where viewers can connect on an emotional level so that they may see the reality of our past and the ramifications in our present. Ida believes the work can be used as an entry point for further study in the curriculum of a student body. His portraits convey a sense of commonality and community shared within the narratives of people’s lives. They offer a unique passageway to learn from history and apply the lessons of the past to solve today’s problems. In the past 30 years, Ida has shown extensively in Europe, the US, and in Asia. He is represented in Los Angeles at the George Billis Gallery, and in Taiwan and Singapore at Bluerider Art.

Bryan Ida

Neighbor, 2018

Ink on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Bryan Ida

Protester, 2019

Ink on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Bryan Ida

Elon, 2019

Ink on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Walterio Iraheta

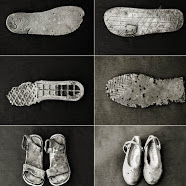

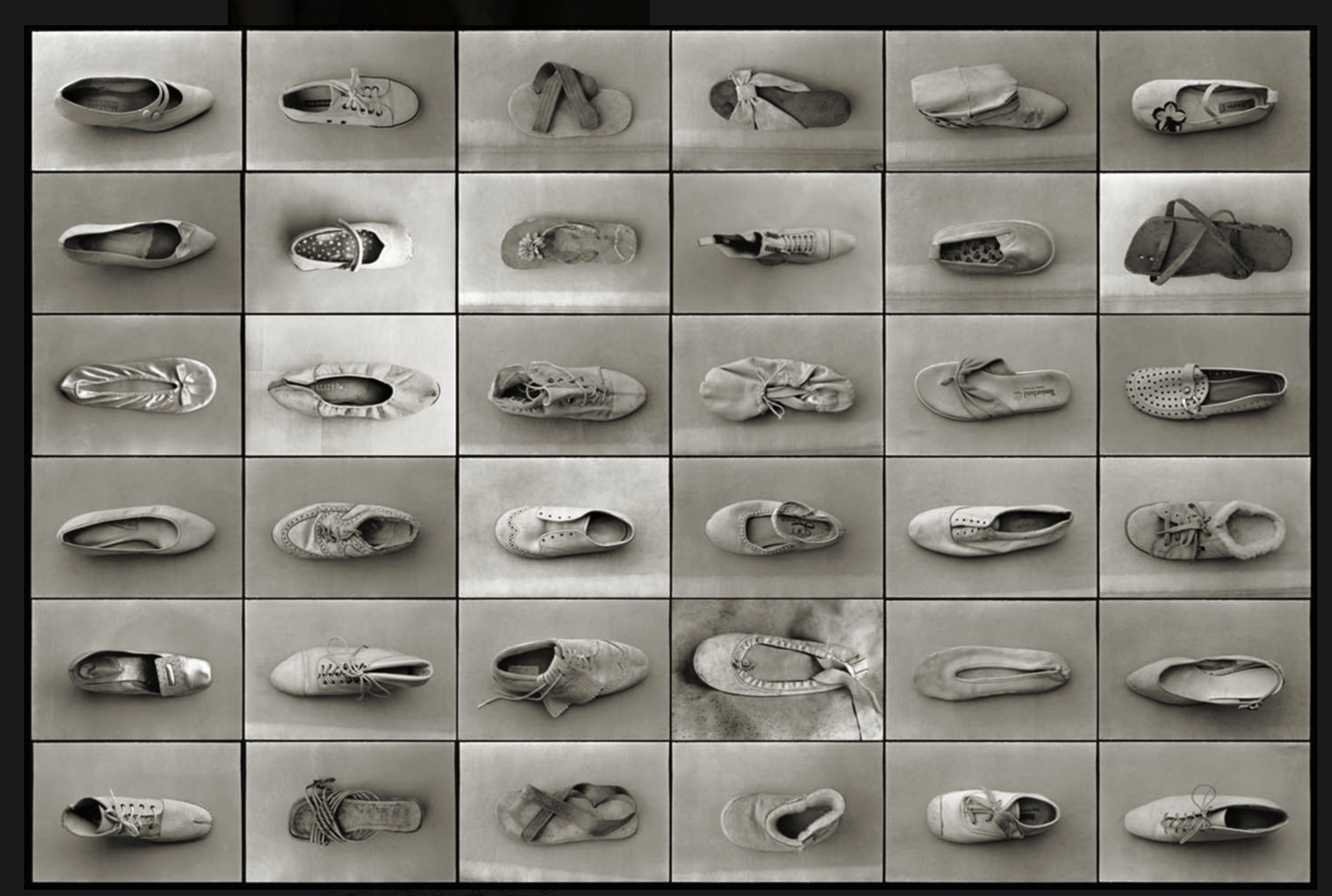

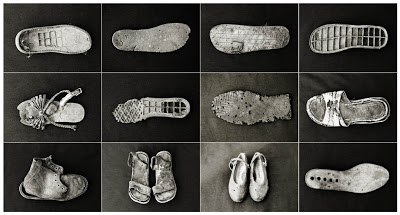

There are people who believe that much can be said about a person by looking at their shoes. By their color, shape, style, how well the shoe is taken care of, how it is made, and the materials used in its manufacture. Some shoes are made by hand by expert craftsmen with skills and methods passed down from generation to generation, made of fine leather, wood, natural fabrics and other organic materials. Others are mass-produced in factories using poured rubber, plastics and other synthetic —sometimes toxic— materials. What is at once a seemingly mundane object, reveals details about its maker, and its owner, in unique and inconspicuous ways, causing this footgear to cease being ordinary, but transformed into an artifact, a portrait, an archive, a memento, of a person, time, and place. Each with its own characteristics and personalities of sorts, these fineries become iconographic signs or symbols reflecting the personality of the person who owns them. The object is a symbol of power, a symbol of belonging, of tenacity, status, class, style, of necessity, of history, of beginnings and of end. The object gives testimony to space and time, place, and person.

My Feet are my Wings is a collective series of photographs of discarded, found and collected objects, primarily shoes, for which exists an analogy between the object, and the human being. The object, interpreted as a form of “living matter”, is capable of evoking feelings and sensations, capable of passing on to us a large amount of information left by it and contained by the energy of the people who participated in its making, and those who will then make use of it. Depictions of discarded objects, particularly footwear, and mostly white shoes, are remarkable for their sense of harmony, visual drama, and narrative content. There are no images of anatomical parts (feet) or celestial figures (wings), but the reference to the existence of a person, or persons, as they relate to the shoes, is metaphorically clear. Although they are not depicted, viewers are reminded that the feet provide support as well as transportation, that shoes can constrain, but also provide protection, and freedom —both physical, and as a form of expression. Oftentimes they are left behind as evidence of human existence —the proof of one’s passage through life— and sometimes, in the end, even lost, or discarded. Due to their personally hygienic nature, shoes are an element of clothing that is rarely inherited, or passed down, so they essentially represent a unique remnant of the owner, much like a fingerprint, an identification card, or a portrait.

Each of Iraheta’s photos embodies the story of a shoe, or shoes, as the main character/s of the work: the shoes are worn, fixed, arranged in order, or simply dumped. Iraheta shows sensitivity for the history of Central America in compositions such as Encontrados (trans. Found), which resembles an archeological showcase of objects unearthed from a mass grave. In these works, the artist took photographs of the strewn-away shoes that were discarded on roads and pathways known as immigrant travel routes northbound from El Salvador, where the artist is from. His invitation to reconstruct the history of these personal migrant journeys is both powerful and persuasive.

Just as some stories make readers feel uneasy, other photographs offer a sense of balance. In Mandala, the monochrome and essential geometric structure of a circle of white shoes bears resemblance to a garden for meditation. On the other hand, his photograph Jardín (Spanish for Garden), in which shoes are scattered arbitrarily over a gray surface, suggests the idea of entropy and disarray, or perhaps, order within chaos. Alternately, these also convey a feeling of freedom and a care-free existence.

In certain ways, this series is also a poetic, nostalgic work: When Iraheta was a boy, his family was severely economically challenged, so owning a pair of shoes was something of extraordinary luck. Generally, they weren’t the shoes that one loved to have, but they complied with his mother’s expectations of durability. One of his most recurring childhood dreams was to see himself arrive home with boxes and boxes of new shoes —Converse All Stars of every color, and perfectly remembering the smell of the new canvas, the rubber sole— then waking in the morning with these sensations still so vibrant and alive. The first thing he would do upon waking was search for them under his bed. Obviously, the only thing he found was his single pair of everyday shoes, ugly and hard. But that beautiful and emotional memory now reproduces a joy and reminiscence that is extended to the sight of abandoned shoes, those buried in the road, or tangled in the telephone pole cables. “I always pick these shoes up when I can, and take them to my studio hoping that at some moment they will talk to me and tell me their story as I get ready to photograph them.”

Walterio Iraheta

Tipología / Typology, from the

My Feet are My Wings series, 2006

36 silver gelatin photographs

on cotton paper

Courtesy of artist and RoFa Projects

Walterio Iraheta

Encontrados / Found, from the

My Feet are My Wings series, 2009

9 silver gelatin photographs

on cotton paper

Courtesy of artist and RoFa Projects

Walterio Iraheta

Exhumación / Exhumation, from the

My Feet are My Wings series, 2007

silver gelatin photographic print

Courtesy of artist and RoFa Projects

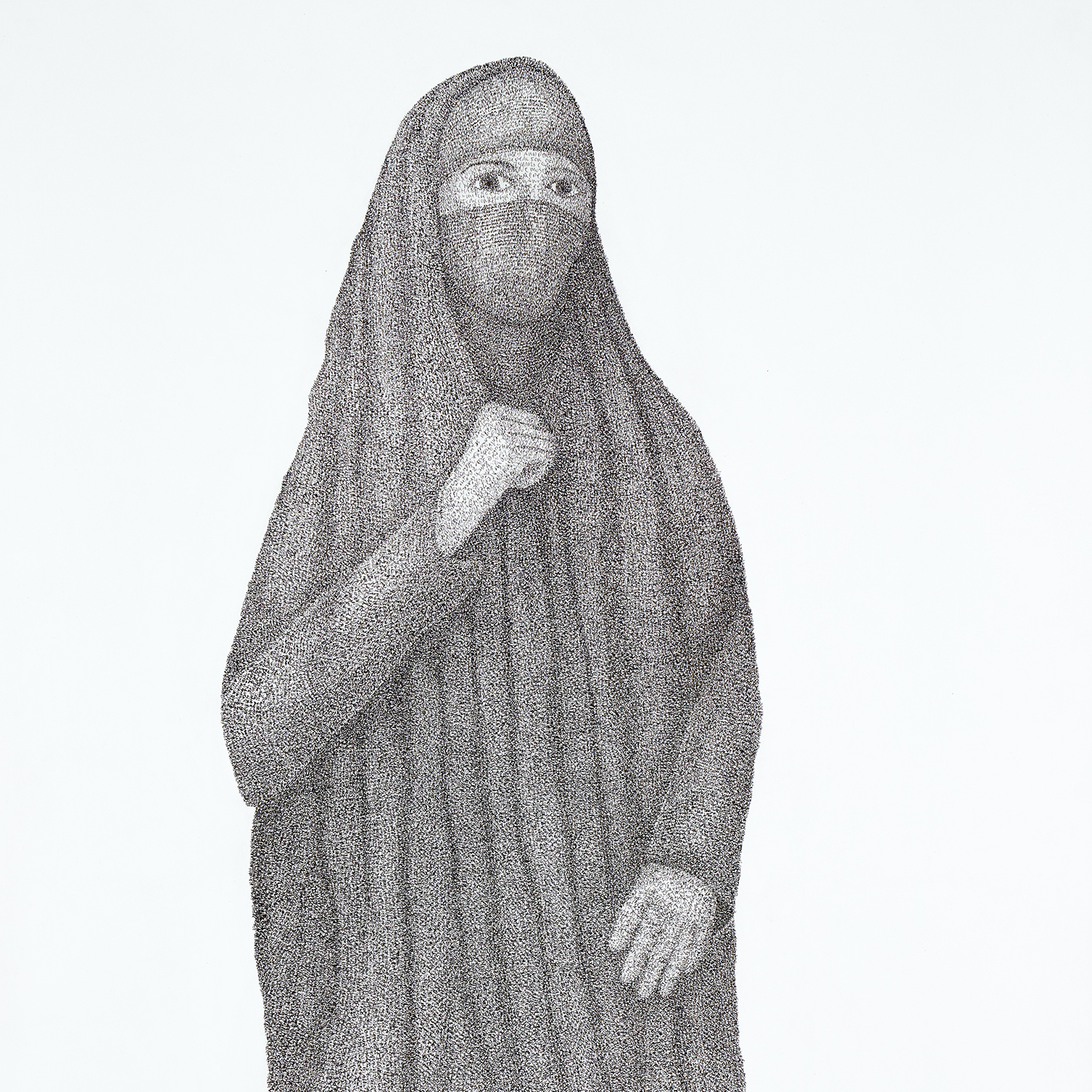

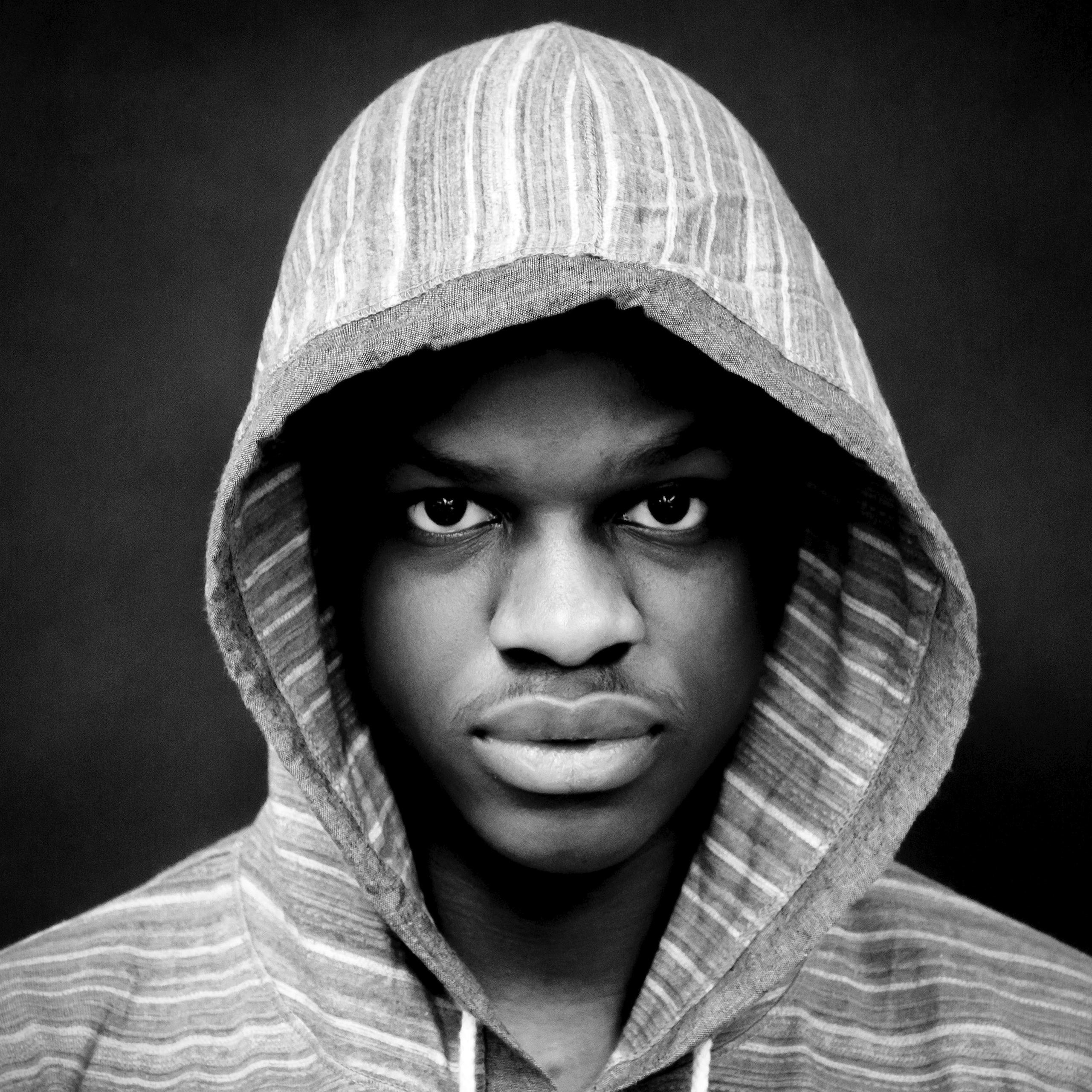

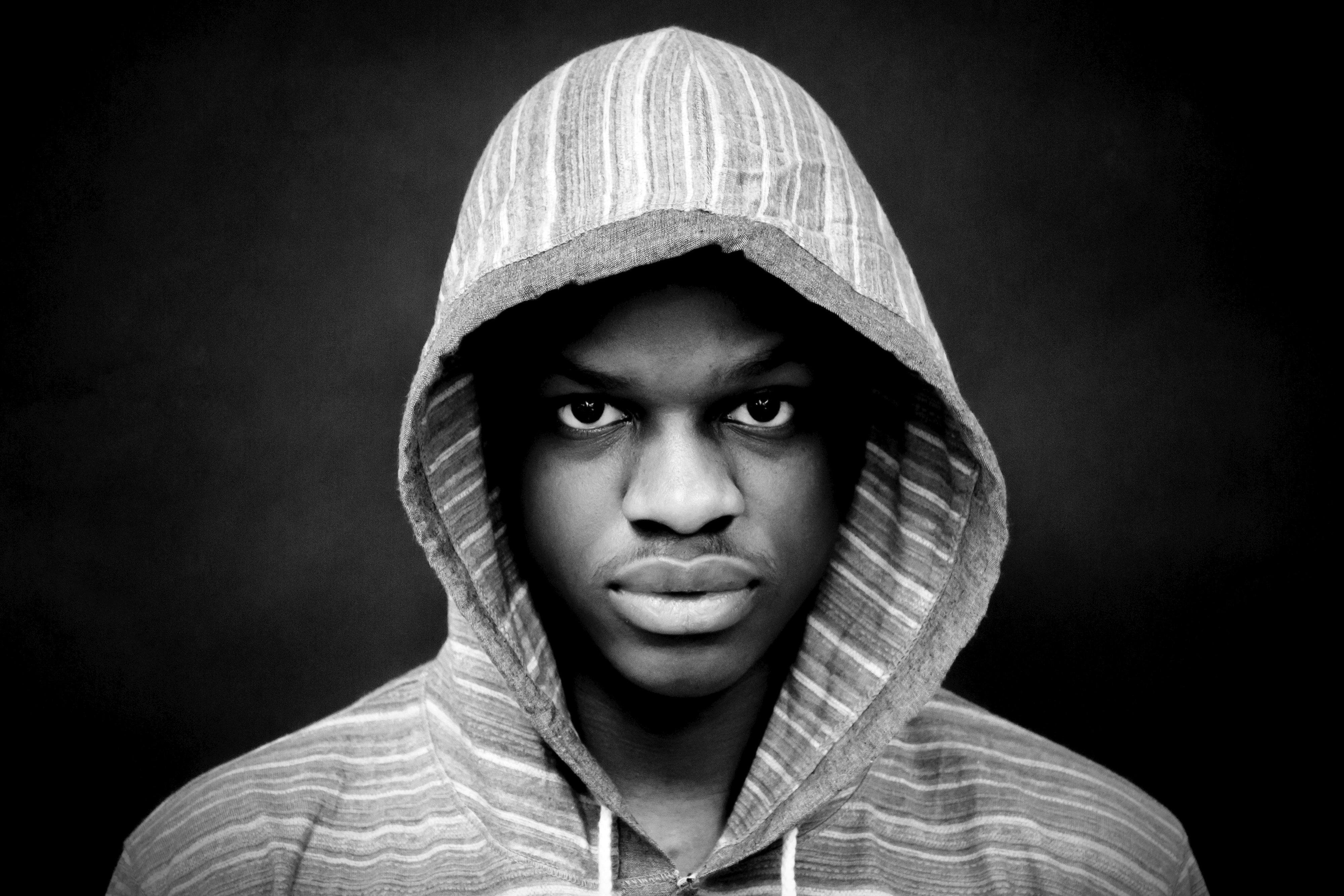

Tracy Keza

Tracy Keza’s work is a cross between fine art and documentary photography that challenges existing stereotypes of the “other.” Through her works, Keza explores notions of identity, oppression, and expression of marginalized communities with a particular interest in societal perceptions and treatment of Black and Brown people.

As a young African woman previously living in America, Keza is particularly interested in how diasporic communities understand issues of marginalization through the lens of intersectionality. Keza believes that representation is an essential part of the ongoing discussion on race, and religion in America, a pivotal part in the fight against social injustices. Keza is committed to the fight against anti-Blackness and Islamophobia. She believes we can better understand our interconnectedness through our shared struggles for equality but only when the diversity of marginalized voices is heard. Keza draws inspiration for her work from Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, American photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier, Deb Willis, and artist JR, and most importantly her daily encounters with the people she meets every day.

In 2016, in collaboration with Studio Revolt, Keza worked to bring Hijabs & Hoodies, her portrait series, to cities with a history of racial profiling, hate crimes, and violence targeted towards people of color and Muslim communities. Some of these cities include Chicago, Oakland, Seattle, Philadelphia, and New York. This multi-disciplinary project is a portrait initiative that questions the dress code for America and the intersection between anti-Blackness and Islamophobia; it explores the stereotyping of African Americans and Muslims, looking specifically at how clothing can be perceived as a threat. Hijabs & Hoodies dissects the intersectionality between race and religion in America and the association of hate crimes between both Black and Muslim communities, specifically Muslim women, and Black men. The project includes an exhibition and an open studio process. Keza sees this series as a community action initiative in which portrait participants become active collaborators in an “open studio” process. In these sessions, informal conversations allow participants to openly share their experiences, concerns, and often compelling personal stories. Keza is seeking participants who question and challenge the detrimental stereotypes of being Black/Muslim or sometimes both. Her goal is to humanize people impacted by a broken system that continues to disenfranchise and disembody Black and Brown bodies. The Hijabs & Hoodies portrait series is rooted in love and solidarity as well as an attempt to subvert and reclaim the very gaze that have made these garments and ultimately these communities “threatening.”

Keza’s black and white portraits are exhibited as giant murals— enormous faces with an unavoidable sense of visibility and presence. She wants viewers to encounter faces and fabrics that draw a range of reactions depending on who views them. The larger-than-life portraits demand the viewer’s gaze and attention. Keza has made the aesthetic choice to work primarily in black and white because she believes that stripping her work of color allows her to focus more keenly on the subject’s humanity and dignity.

Tracy Keza

Andrew, 2016

from the Hijabs & Hoodies series

monitor installation

Courtesy of the artist

Tracy Keza

Miriam, 2016

from the Hijabs & Hoodies series

monitor installation

Courtesy of the artist

Tracy Keza

Fatima, 2016

from the Hijabs & Hoodies series

monitor installation

Courtesy of the artist

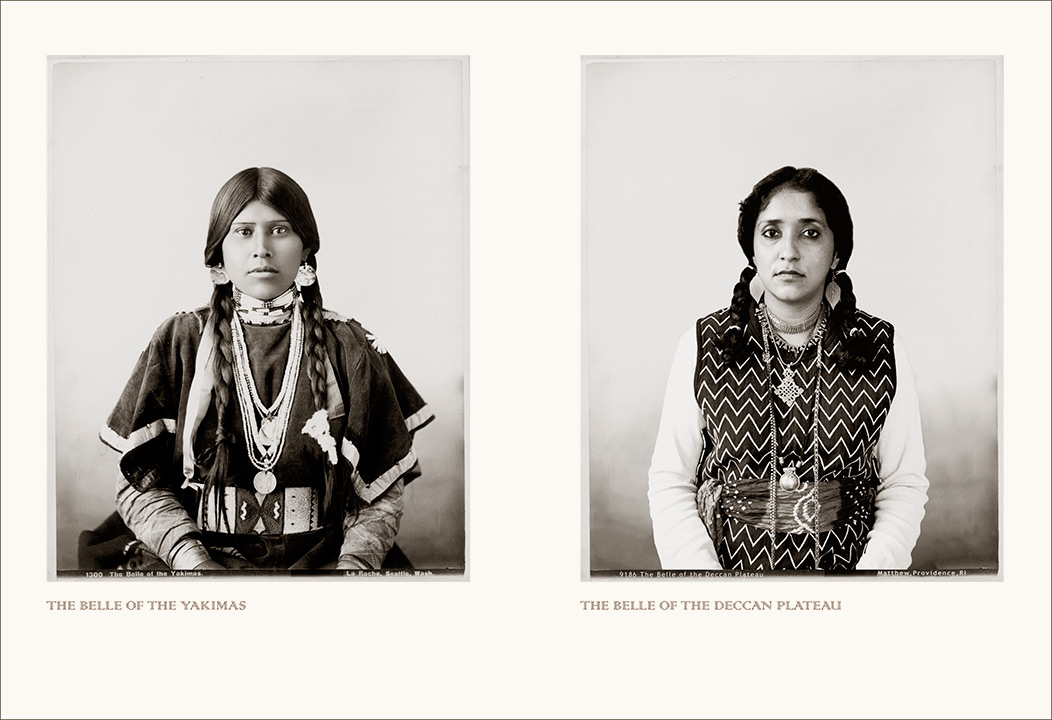

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew

As an immigrant, Annu Palakunnathu Matthew is often questioned about where she is “really from.” When Matthew says that she is Indian, she often has to clarify that she is an Indian from India. Not an American-Indian, but rather an Indian-American, South-Asian Indian, or even an Indian-Indian. It seems strange that all this confusion started because over 500 years ago Christopher Columbus thought he had found India, and in turn, called the native people of America collectively Indians.

In this portfolio, Matthew looks at the other “Indian”. She finds similarities in how 19th century photographers of Indigenous Americans looked at what they called the “primitive natives”, similar to the colonial “white gaze” of the 19th century British photographers working in India. In every culture, there is what we call the “other”.

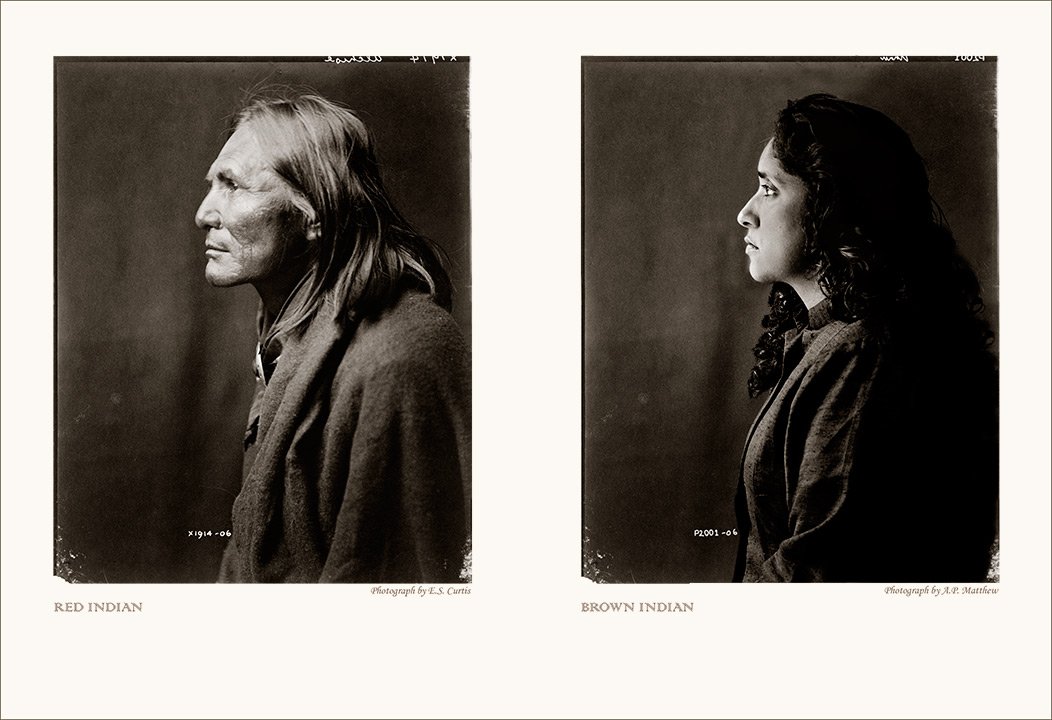

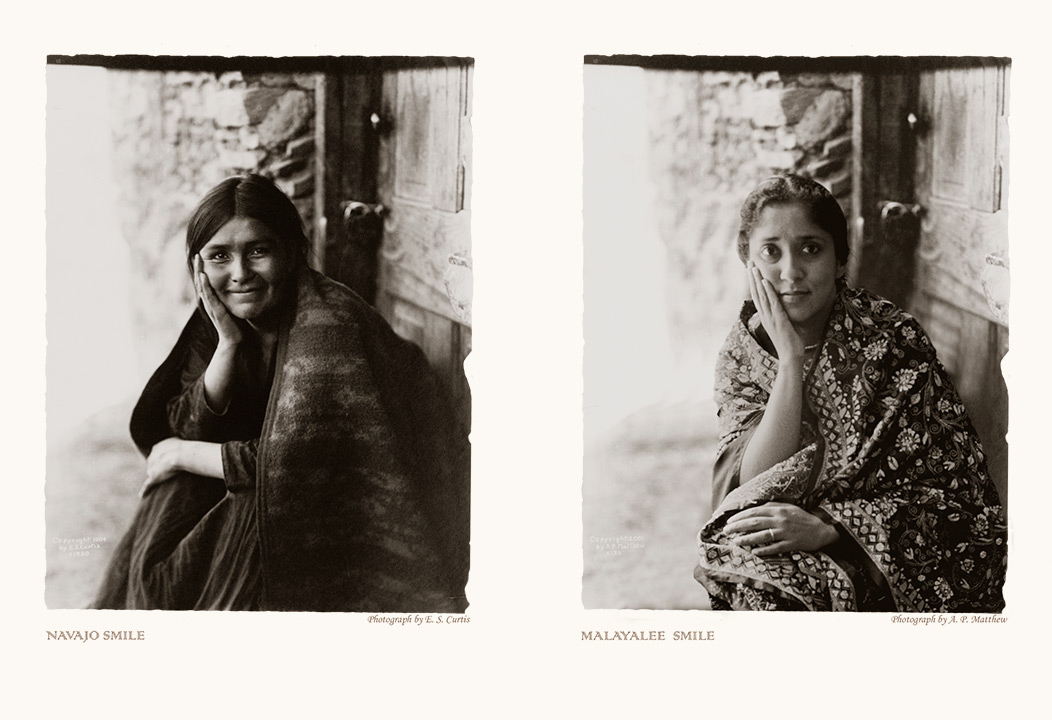

Matthew plays on her own “otherness”, using photographs of Native Americans from the late 1800s through the early 1900s, which perpetuate and reinforce stereotypes. The images highlight assimilation, use labels, and make many assumptions. She pairs these, with current day self-portraits of the artist herself, in clothing, by posturing, and creating environments that mimic these archival, older images. The clothes, or costuming, are also “made up” or appropriated. Matthew’s fictionalized history is similar to how Edward Curtis —one of America’s 19th century premier photographers and ethnologists— did with the intervention in his subjects’ posing, and the “dressing-up”, of some of his native indigenous subjects in “native garb” in his photographs, that may, or may not, have been accurate representations of the peoples photographed.

Matthew’ performative work —by inserting herself as the subject— is not a new concept in art. Not unsimilar to how Cindy Sherman’s well-known 1990s photographic series —depicting herself in many different contexts and as various imagined characters from art history, or the Golden Age of Hollywood— were initiated. By juxtaposing many famous Western photo-archives like Curtis’ from the Library of Congress, and other institutional special collections, with self-performative work like Sherman, Matthew challenges the viewers’ literal assumptions of “then and now”, “us and them”, “exotic and local”— time, people, place.

As Holland Cotter of the New York Times wrote about her 2016 solo exhibition at sepiaEYE in New York, “...the mostly album-size photographs in this compact but far-ranging gallery survey are about the intensities and confusions of a cultural mixing that makes the artist, psychologically, both a global citizen and an outsider, at home and in transit, wherever she is. And it’s about photography as document and fiction: souvenir, re-enactment, and imaginative projection.”

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew

Nose Rings, from the

An Indian from India series, 2001

Archival digital print

Courtesy of the artist and sepiaEYE, NY

Original photo courtesy of The Library

of Congress, Washington, DC. Kaw-Claa. Thlinget native woman in full potlatch dancing custome [sic], ca 1906.

Photographers: Case & Draper

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew

Red/Brown Indian, from the

An Indian from India series, 2001

Archival digital print

Courtesy of the artist and sepiaEYE, NY

Original photo courtesy of

The Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Alchise, Apache Indian, ca 1906.

Photographer: Edward S. Curtis

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew

Smiles, from the

An Indian from India series, 2001

Archival digital print

Courtesy of the artist and sepiaEYE, NY

Original photo courtesy of

The Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

A Navaho smile, ca 1904.

Photographer: E.S. Curtis

Installation View, Title Wall. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Front West Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Front West Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Front West Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Front East Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Front East Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Corridor of Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Corridor of Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Back Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Back Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Installation View, Back Gallery. Black, White & Shades of Grey Exhibition, Jan. 18, 2022 to Mar. 27, 2022.

Claudia Casarino Artist's Panel

Mark Steven Greenfield Artist's Panel

Walterio Iraheta Artist's Panel

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew Artist's Panel

About the Virtual Exhibition

About the Virtual Exhibition

The Black, White, & Shades of Grey Virtual Exhibition is an online exhibiton. You will be able to navigate this virtual exhibition without downloading any files.

Click the buttons below to be linked to the virtual exhibition! The first button has tags, or labels with information regarding each artwork and artist. The second button has no tags.

Virtual Exhibition with Tags Virtual Exhibition without Tags

Navigation

Using a mouse, click and drag to navigate throughout the exhibition. The circles on the floor are the points where you can stand. Use the mouse wheel to zoom in and out. To find more information on the artwork, click the colorful circles by a piece to open up a tag.

Claudia Casarino

Claudia Casarino

![Annu Palakunnathu Matthew Nose Rings, from the An Indian from India series, 2001 Archival digital print Courtesy of the artist and sepiaEYE, NY Original photo courtesy of The Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Kaw-Claa. Thlinget native woman in full potlatch dancing custome [sic], ca 1906. Photographers: Case & Draper](https://www.cpp.edu/kellogg-gallery/exhibitions/2021-black-white-and-shades-of-grey/annupalakunnathumatthew/kaw-claa-with-nose-ring-and-annu-with-nose-ring.jpg)